Lives built on false pretenses and erroneous views are destined to fall, like sand castles standing before ocean tides.

Manshi Kiyozawa knew such truth, his life ravaged by disease, job loss, the death of loved ones, and gnawing poverty. Yet, spiritually he stood strong. He wrote: “The most important thing is that we should find firm ground for our spirit to strike root in. We can build houses only on firm ground. Our spirit cannot stand firm if it has no foundation.”

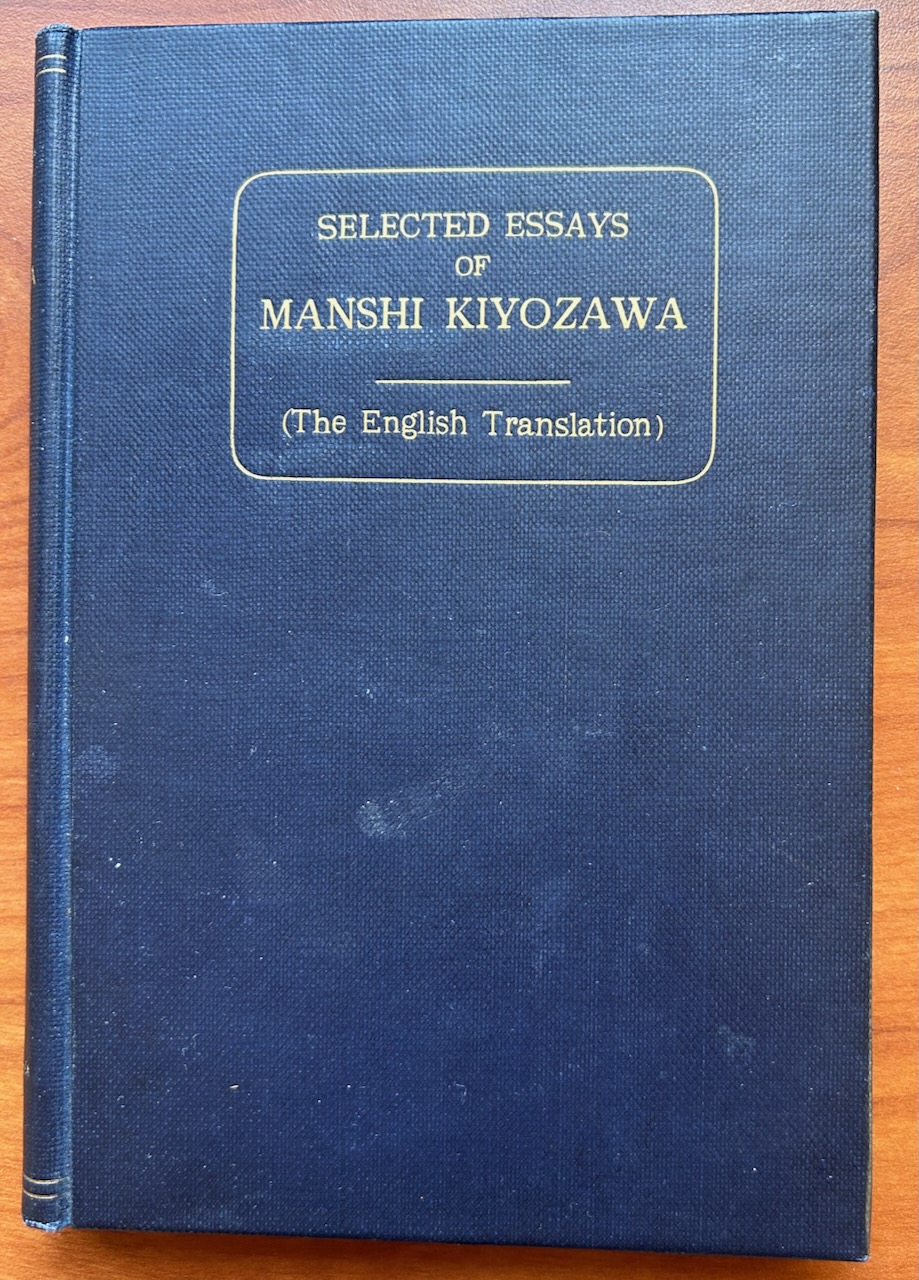

Despite grueling hardships, Kiyozawa (1863-1903) explored how the mind works, the nature of faith, the meaning of happiness, and other important philosophical questions which helped make him one of the most influential Buddhist thinkers in modern times. In 1936, several of his essays and diary entries were translated by Kunji Tajima and Floyd Shacklock in a book, “Selected Essays of Manshi Kiyozawa, The English Translation,” published by Bukkyō Bunka Society in Kyoto.

“Among the many excellent Buddhist priests who labored in the Meiji era, the Rev. Manshi Kiyozawa shines like a bright star at dawn,” wrote Buddhist scholar Shūgaku Yamabe (1882-1944) in the book’s forward. “His noble character, his keen insight, and his deep religious experience will make him stand on the highest peak for making the modern Japanese people who have received the culture of Europe and America, recognize Buddhism in its new shape without destroying its old and right tradition.”

Kiyozawa lived when Japan just emerged from centuries of feudalism, beginning its transformation to a modern society. A student of Western philosophy, he used critical analysis and rational thought to make sense of Buddhist teachings, which was mired in archaic language, literalism, tradition and superstition. His views revitalized Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, sparking debate, study, and fresh thinking, inspiring a lineage of innovative teachers such as Haya Akegarasu, Daiei Kaneko, Ryōjin Soga, and Rijin Yasuda.

He pondered the nature of “faith,” an important Jodo Shinshu concept, and how it might work. He wrote:

Faith in others is the recognition of sincerity in another’s heart, the discovery in another of the sincerity which is as firm as a huge rock. Our faith in our parents means that we recognize sincerity in them. Because we feel sincerity in our friends, we put faith in them. So, when we believe in others, we feel our spiritual foundation has been made the more solid and enlarged. Consequently, we feel that the source of our activity becomes greater and stronger. Thus, our power grows before we are even aware of it.

Emphasizing introspection, feelings and personal experience, Kiyozawa led a movement called “Seishinshugi” (精神主義) (literally, spiritualism) as a way of understanding life through the Buddhist teachings. To follow this path, confronting oneself with brutal honesty and sincerity is utmost essential.

He wrote:

What then is that foundation? It is not wealth, nor power, nor social standing, nor learning. It is sincerity… Sincerity will not burn in the fire, never corrode in water. No robber can take it away. No disease can destroy it. A drawn sword cannot kill it. It is constant, immovable, unshakable, imperishable, and so firm that even a great rock is not comparable to it. When you find this firm sincerity, then and there for the first time you have the very ground for your spirit to rest on.

Introspection is key. “The presence or absence of anxiety and care in your mind must be closely watched,” he wrote. “Here lies a secret of spiritualism; that is, spiritualism considers every worry and pain as an illusion born of our evil thoughts… Even when we seem to be suffering annoyances from outside men and things, we are really not molested in the least by the outside world, but only by our own evil thoughts.”

“Kiyozawa encountered many difficulties and disappointments in his life, but he used these various experiences as opportunities to reflect deeply within himself,” wrote Shin’ya Yasutomi, in his essay, “The Way of Introspection: Kiyozawa Manshi’s Methodology” (The Eastern Buddhist, Vol. 25, No.1/2, 2003).

For Kiyozawa, introspection means self-examination. Yasutomi wrote:

It is not meant to culminate in a state of other-worldly bliss, in which the self is totally forgotten. Instead it refers to a way of reflecting inwardly on oneself in order to realize that one is a deluded finite being, laden with raging blind passions. This contrasts sharply with the approach to self-examination in which one’s self is not made the object of careful investigation or criticism. Yet neither does self-examination refer to the process whereby the self is analyzed theoretically. As Kiyozawa states, “To examine the self through the process of self-cultivation means to examine how one is actually acting. To do this is none other than introspection.”

The quest for truth was pressing and urgent for Kiyozawa. He suffered from tuberculosis—at the time an uncurable disease—the specter of death constantly hanging over his head. Pondering one’s thinking process, he wrote:

When we are asked why there are such evil things as poisonous adders or wicked dragons in the world, our spiritualism has an answer. It would contradict our most fundamental principle to admit the independent existence of evil or wickedness: a wicked dragon or a good one, a viper or a snake whose flesh has medicinal value, are all the product of our own mind which has full liberty in such a situation to call a thing good or bad… From our viewpoint, a certain thing cannot be poisonous or bad only in its objective existence but it must also be evil in its subjective existence. Anything can be evil or bad when our mental development is imperfect. In other words, evil belongs entirely to our mind, and not to the external world, as far as our spiritualism is concerned…

Wine cups of precious stones, ivory chopsticks, and lofty halls to sleep in; these our common thought aspires after. We scorn simple food, wine from a gourd, or a dwelling on a dirty by-street. We honor people riding in fine carriages carrying affairs of state on their shoulders, and in the fields. It is rather the way of the world that dirty by-streets are despised and lofty halls respected; straw-sandalled figures are disdained and fine carriages honored.

If we really aim at stability of mind in this changing world, we must get away from the pleasure and pain of fine residences and dirty hovels. We must accept our present life just as it is, whether we are living in large mansions with all comforts around us, or working laboriously in small houses on dirty by-streets. Our interpretation of life should start from a complete acceptance of this present life. In other words, we must find our contentment in our own daily living. And in no other way but in spiritualism can this end be attained.

But our first concern is how spiritualism can solve this pressing question. The strength of spiritualism is based on our firm belief that Truth pervades every nook and corner of the world. If the omnipresence of Truth is thus accepted, we are compelled to admit that Truth is present both in our subjective and objective worlds. And, because of the Truth in the objective world, it is evident that our consciousness of subjective Truth must precede our awareness of objective Truth.

As spiritualism is nothing but our consciousness of subjective Truth, it is the conviction of spiritualism that our subjective experiences can reach to the heights of perfection. We are constantly annoyed by our own evil thoughts which prevent us from regarding all objective things as of the same level (that is, we are making comparisons between this thing and that). Yet finally we shall see the inadequacy of such thinking and come to know that when our subjective experience fully attains to perfection, outside things in themselves are neither noble nor base. Then we shall see that an unkempt street is not unkempt at all, but only that our own view itself is unkempt. Those poor sandals are not lowly in themselves; it is our own mind, which looks down upon them, that is lowly.

With such realization, Kiyozawa felt “we shall not only be without dissatisfaction with our surroundings, but we shall find unlimited enjoyment in any place, that will make us satisfied in all places. “

Key is understanding one’s subjective recognition of the objective world, which in terms of spirituality, recognizes value, quality, and beauty in material civilization. He wrote, “The culmination of the activities of spiritualism is seen when the same value, the same interest, the same quality and the same beauty are recognized in all things in the world. This service of spiritualism is indispensable in protecting us from all ruinous rivalries and struggle and saving us from luxury and waste.

This viewpoint later was adopted and elaborated on by art critic Sōetsu Yanagi, who found splendor in the ordinary, which he called “the Pure Land of Beauty.” Yanagi (1889-1961) was a Japanese philosopher, art critic, and proponent of folkcrafts, whose essay, “The Pure Land of Beauty,” was published in English in The Eastern Buddhist journal (1976).

Yanagi wrote:

When we look at nature which surrounds us, for example, grass and stones, not to speak of flowers or butterflies, we discover there is not a thing which is ugly. There, all things are beautiful in their true state. Although some of us might consider certain things less beautiful than others, such judgement is based on self-centered human ideas. In nature itself, ‘ugliness’ is inconceivable. It is human convenience that man discriminates, but in nature, the difference between the high and the low, beauty and ugliness has no meaning.

Yanagi cites the Sutra on the Buddha of Eternal Life, which describes the “non-existence of duality of beauty-ugliness.” The Pure Land of Beauty does not belong to the world of relativity. In the absence of duality, beauty emerges. Ultimate beauty becomes impossible apart from nonduality. The dichotomy of beauty-ugly disappears.

Kiyozawa also considered the finite nature of the self versus the infinite nature of the universe. Shacklock, a Christian scholar, in his book’s translation, used the term “Absolute Being,” a nuance that could imply god, although later translations of Kiyozawa’s work merely use “Infinite.” He wrote:

Our only basis in this life is in an Absolute, Unconditional Being. There is no need here to ascertain whether that Absolute, Unconditional Being lives within us or outside, because the Absolute Being resides wherever seekers meet it. We cannot positively declare that it lives within us or without. What we can say here is that we shall not be able to find a true philosophy of life until we meet this Absolute Being.

Spiritualism seeks to bring contentment within our own mind. It never permits us to be distressed by following external things and other men. Sometimes this spiritualism seems to be following external things and men, but this does not come from a sense of need. Those who rely on spiritualism and who feel a sense of inadequacy should seek their contentment in the Absolute Being, not in external things or among men, for the latter are all finite and limited.

Spiritual peace means grasping the relationship between self and the infinite, translated as “power beyond the self” or “Other Power.” Kiyozawa wrote:

Spiritualism is, in short, the first need in our daily life. It comes to us when we realize that complete happiness is found within the bounds of our own mind. In its expression in the world, spiritualism never brings trouble on itself by following external men and things.

Our spiritualism holds that we can find contentment within ourselves. On casual view, spiritualism seems to be omnipotent within itself. But in reality, it is nothing of the sort. It relies on Other Power.

Following this line of inquiry, Daiei Kaneko, a student of Kiyozawa, quotes his teacher: “The basis for religion is reverence arising in man standing before the Absolute, realizing his limitations, and taking refuge in the Infinite.” In taking refuge, Kaneko points to how one’s mind becomes settled and finds peace.

Rijin Yasuda also wrote about the self, “I” versus “Other” or “Thou,” and “finite” time versus eternity. Referring to nenbutsu, reciting Amida Buddha’s name, Yasuda explained this name indicates, not an object, but rather a “relationship.” Yasuda wrote:

It indicates the relationship of I and Thou, not the existence of something. However, that relationship is not the relationship of one thing to another; it is the relationship between that which has form and that which does not. It indicates the relationship of time and eternity. The relationship is always mutual.

As Kiyozawa explained:

This spiritualism is a practical doctrine which develops at the point where the relative enters into the absolute, where the limited meets the unlimited, where the finite meets the infinite. These words, “enters into” and “meets,” are almost beyond explanation; but in order to show that our spiritualism relies on Other Power, we must use them to distinguish between Other Power and self-exertion. Where “the relative enters into the absolute” and “the finite meets the infinite,” there we explain the absolute by means of the relative and the infinite by the limited. Then we can say that this so-called contentment within ourselves is a gift bestowed on us by the absolute and the infinite.

We must not forget the light of this absolutely unlimited truth. We must keep an eye on the light. As the light is no other than the sincerity which is boundless in its extent, we are gradually led into a belief in this light only if we keep our eyes fixed upon it. We can then rely on the light and enjoy peace in it. As the light enfolds us and carries us completely away from the worries of the world, we can recognize the light vividly on everything on the earth. Countless things in the world, all different in their appearance and size, will be seen to be expressions of this absolute light of unlimited strength.

With such words and thoughts, Kiyozawa brought fresh meaning and new relevance to traditional Jōdo Shinshū teachings for people living in modern times.

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America