Understanding Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in modern terms began largely thanks to certain influential teachers from the Higashi Honganji denomination. They include Manshi Kiyozawa, Ryojin Soga and Daiei Kaneko. Perhaps the most colorful and controversial was Rev. Haya Akegarasu.

Akegarasu (1877-1954) was a direct student of Kiyozawa (1863-1903), living and studying with him in Tokyo, editing his journal called “Seishin-kai (Spiritualism) and eventually becoming Higashi Honganji’s head administrator. Later, Akegarasu recalled how he’d explain to his teacher some thought, concept or understanding, but always Kiyozawa would refute, dismiss, and “crush” him. “It was such an unimaginable crushing that I felt he must be an atheist,” Akegarasu wrote. “He crushed and crushed and completely crushed me. He never let me hang onto anything.”

Consequently, Akegarasu came to feel a sense of spiritual liberation, in his words, not reliant on Buddhas, gods, philosophy, or religion. He wrote, “There is no Pure Land or Zen or Buddhism or philosophy. Nothing to occupy. Nothing to be attached to. Nothing controls me. I was raised as a real, free man. And I am deeply grateful. I have nothing to fear in this world.”

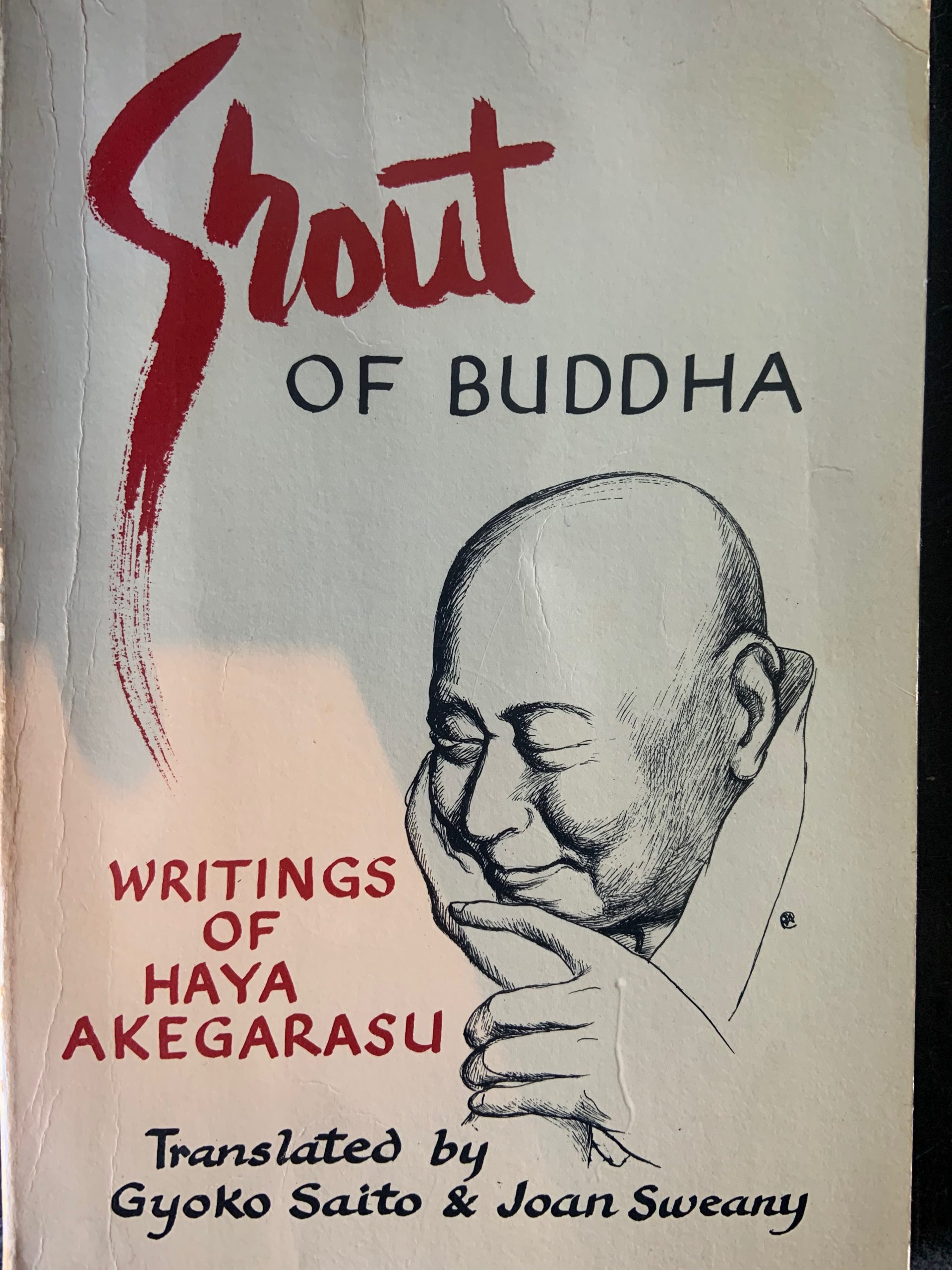

Much of the information I cite here comes from the book, “Shout of Buddha, Writings of Haya Akegarasu,” translated by Gyoko Saito and Joan Sweany, published in 1977. Rev. Saito studied with Rev. Akegarasu and later served at Buddhist Temple of Chicago, Los Angeles Higashi Honganji and Higashi Hongwanji Hawaii District. To me, the title “Shout of Buddha” really shows Akegarasu’s vitality, conjuring a dynamic, exploding life force, in sharp contrast to Buddhism’s image of passive quietude.

Akegarasu and Kiyozawa lived in a time when Japan was emerging from two centuries of feudalism and isolationism which had just broken apart. Jodo Shinshu had become a moribund religion, bound by government policies promoting stability and predictability, emphasizing tradition and ceremony. As Japan opened its borders to international trade, new ideas streamed in, enabling Kiyozawa to learn Western philosophy and thought, which he used to inject Shinshu with fresh understanding, while discarding traditional words and explanations.

“In looking at Reverend Kiyozawa and Reverend Akegarasu, the fact to notice is that they abandoned the thousand-year old Buddhist terminology and used ordinary words to manifest Buddhism,” Rev. Saito wrote. “In order to do that, they had to translate the teaching with their own flesh and blood. Thus, Buddhism was reawakened at a most critical period in the history of Japan… Akegarasu manifested the life of his own flesh and blood that are a never-ending great shout.”

Akegarasu learned from Kiyozawa that spiritual understanding must be felt in one’s bones, rather than discussed and debated. A natural writer, he poetically expressed these feelings clearly and strongly. In his essay, “Declaration of the Independent Man,” Akegarasu writes: “Note well the free shout of the independent man, his lonely mind, his feelings of longing, his figure which is most strong and most weak. Taste the new world of life you will find here, a world created after deep introspection, by the total annihilation of self. There is no room for seeing evil or for prayers to gods; there is no so-called morality and no so-called religion. There is only living, enjoying, struggling—as a person, as what I am. Note carefully my strengths and weaknesses.”

Among my favorite writings is a tale he wrote called “The Solitary Pine.” Writing from the perspective of a great pine tree standing in a large field, the tree tells its life story to a Buddhist priest in a dream. The tree recounts how other nearby trees grew faster, stronger and taller, but inevitably were cut down by loggers. Before they left, they bragged about becoming lumber for large temples or government buildings, only to disappear over time. This pine tree had crooked branches but continued growing by itself in the field. Alone, it weathered great storms, snow, floods and violent earthquakes, fighting feelings of deep loneliness. At times with no other choice, woodcutters would come to cut down the pine tree, sparking feelings of terror in it. From the depths of its being, a great energy surged forth “To live!”, moving the universe and scaring off the woodcutters. The tree has lived more than a thousand years and now provides shade to travelers and home to birds.

“Shout of Buddha” translator Joan Sweeny recounted how she first heard “The Solitary Pine,” during a time of “great darkness in my life.” She wrote, “In my confusion and depression, I heard a bright, cool, joyous voice. Through the barriers of language, in a capsule version, Akegarasu spoke to me clearly. The life of the pine tree came to me as the most vivid possibility of what my life too could be.”

When I first read Akegarasu’s writings, I didn’t know what to make of him. Honestly, he seemed like an egotist, always talking about himself. I think I now understand where he’s coming from. Jodo Shinshu and other forms of Buddhism often become doctrine-like teachings that people espouse, debate and become attached to, encumbering their thinking. In this way, people even think the Buddha is their savior. However, all Buddhism is supposed to be upaya, “expedient means,” like a raft getting us across the river to understanding. Somehow that raft has become a possession, something to obey, hide behind, or rely on. Akegarasu wants to crush it.

Likewise, any sense of “self” that Akegarasu felt, any sense of accomplishment or understanding, I think Kiyozawa wanted to “crush.” As Akegarasu said, his teacher “crushed and crushed me,” until nothing was left except complete liberation.

For Rev. Akegarasu, life itself is most precious. Everything else just stands in the way. He points to a flower: “I hold here a single violet. The Kegon Sutra, Lotus Sutra… Bible, Upanishads, Analects of Confucius—none of them can compare to this single violet. Things made by a person’s hands or words that come out of his mouth are always secondary as compared with the person himself. Something that is made cannot compare with something that is born.”

Rev. Akegarasu wrote: “Not to lean on anyone else, or on any God or Buddha; not to tremble before destiny or become tangled up in circumstance: to grow into real independence! I recorded the birth cry of the liberated soul and traced the form of the free man… Look at truth. Talk truth. Throw away those conventional rules which don’t help at all. Touch life the way you want to. Inevitably, all people must make their Declaration of Independence along with me.”

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America