By Rev. Ken Yamada

Jodo Shinshu uses words such as “salvation” and “save” which make me uneasy. They give Pure Land Buddhism the appearance of a Christian-like religion with Amida Buddha as savior.

Yet, Jodo Shinshu’s founder Shinran Shonin used these terms. In the Tannisho, he says:

As for me, I simply accept and entrust myself to what my revered teacher told me, “Just say the nembutsu and be saved by Amida”; nothing else is involved.

Elsewhere in the Tannisho, he says:

To begin with, then, it is through Amida’s design that we come to say the nembutsu with the belief that, saved by the inconceivable working of the Tathagata’s great Vow of great Compassion, we will part from birth-and-death.

Throughout his master text Kyogyoshinsho, Shinran writes about being “saved” and “salvation.” He quotes the Larger Sutra on the Buddha of Infinite Light, where Amida Buddha vows:

Those impoverished- I will save universally and relieve of all suffering…

In Notes on Essentials of Faith Alone, he writes:

It is evident that Amida, distinguishing every sentient being in the ten quarters, guides each to salvation…

As a Buddhist minister, I avoid using “saved,” “salvation,” “savior,” or any term that might make Jodo Shinshu seem more Christian than Buddhist. It’s hard enough explaining Shinshu when key elements are Amida Buddha (“savior”), Amida’s Vow (sometimes translated as “Amida’s prayer”) and Pure Land (heaven-like place). Perhaps synonyms for “save,” such as “set free,” and “liberate,” especially when related to mental suffering, make more sense.

Yet, these salvation-related words are the “elephant in the room.” Many of us abhor them. What do they mean and why did our esteemed teachers from the past use them? I think it’s an important discussion and worthy of study. Let me take a stab at making sense of them.

I found clarity in the writings of Kaneko Daiei (1881-1976), an innovative Buddhist scholar who followed Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903) in analyzing and comprehending Jodo Shinshu in modern terms. In a 1915 essay, “Rennyo the Restorer,” Kaneko wrote how the second founder of Jodo Shinshu brought Shinran’s message of “taking refuge” in Amida and being “saved” into greater focus.

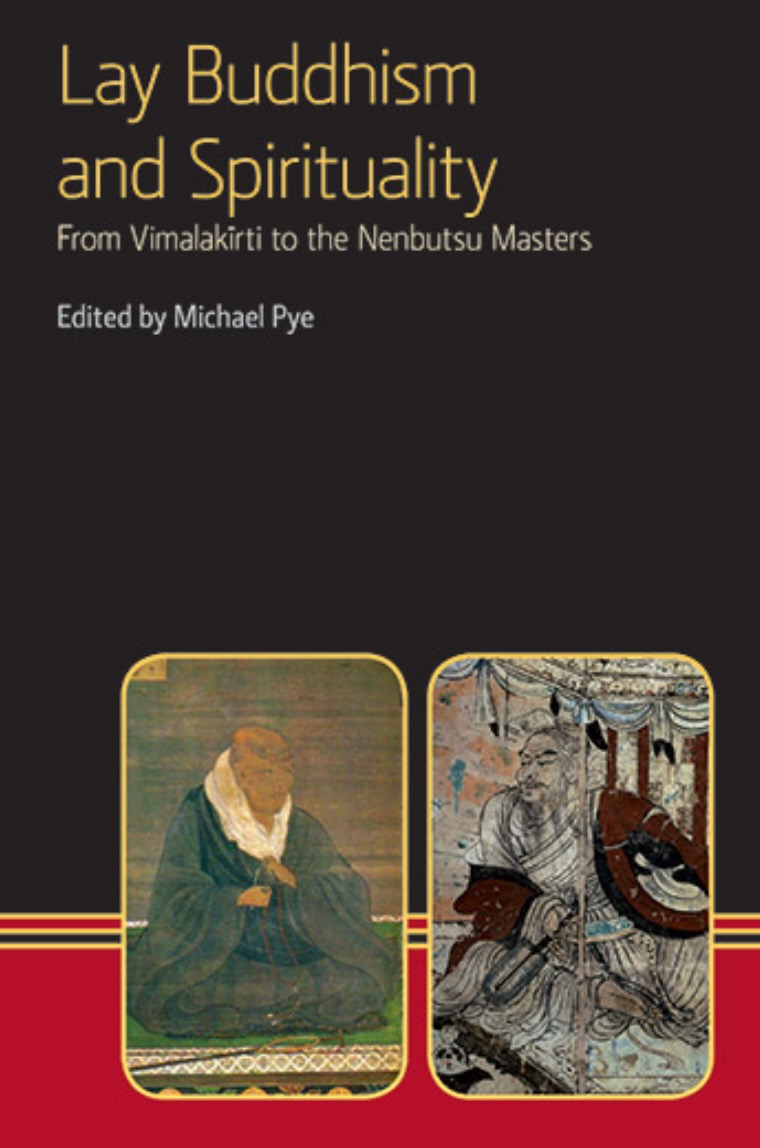

An English translation from Japanese of his essay first appeared in a 1998 edition of the Eastern Buddhist journal, which was reprinted in the book, “Lay Buddhism and Spirituality, From Vimalakīrti to the Nenbutsu Masters,” edited by Michael Pye (Equinox Publishing, U.K., 2014)

Kaneko wrote: “It is due especially to Rennyo that the formulation to implore the Buddha, saying, ‘Amida, save me in the life to come,’ came to earn the high regard it did.”

He continued:

If we gave thought to the matter, we would find that the self we think we know is only apparitional; the real self is something we know nothing of. For this reason, we float through life in a dream; we deceive ourselves, thinking it our fate to paddle about, never reaching solid ground. Clinging to wife and child out of attachment to dear life, we strive to extend our life as long as possible. We add to the larder our aspersions to wisdom and good; we want to believe that we harbor deep in ourselves the light of inner convictions to see us through bad times.

But religion challenges our notions, saying: Be yourself, throw down that mask, reflect on who you really are. For those who truly wish to live, this is what must be done: admit the vanity of your knowledge and deeds, and confront the darkness and ignorance of your own soul… When it comes our time to confront this ultimate source of despair, there is no turning to wife or children or worldly possessions for consolation. At this final impasse we learn the truth that man, born alone, dies alone.

Forced to face the darkness of our own soul, there is one thing this miserable portrait of self elicits from us: the desire to be saved. With our entire being focused toward that one purpose we implore the powers that be, “Buddha, save me,” and we stand ready to give everything—all our worldly possessions—if only the Buddha would “Save me in the life to come.”

To better relate this discussion to everyday life, allow me to describe my wife’s experience. Some years ago, she suffered an illness causing overall muscle weakness and periodic breathing problems. One night, she had an acute attack, so we rushed to the hospital. However, the drive was especially long over a bridge to San Francisco. Traffic was heavy. My wife, worried and gasping for breath, frantically wondered if she’d make it to the hospital. Almost subconsciously, she started reciting nenbutsu, “Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Amida Butsu.” Indeed, this was her cry for help. Suddenly, the image of the Amida statue in our local temple appeared in her mind. Seeing Amida’s peaceful face, she felt a sense of relief. She thought, “Whatever happens is up to Amida.” She calmly rode the rest of the way.

In case you’re wondering, my wife is not a fervent Buddhist given to visions. Besides for somewhat regularly attending Sunday services, she isn’t particularly religious. Yet she reflexively recited Amida’s name in her time of crisis. From this standpoint, I think Kaneko’s words make sense. When facing suffering from which we cannot escape via our own power, a natural human response is to call out for help.

In Jodo Shinshu, I think “seeking help” or “accepting help” may be defined as “taking refuge” or “bowing down.” Kaneko quotes a letter (V. 9) by Rennyo:

In our tradition the meaning of settled mind is wholly expressed by six characters, NA-MU-A-MI-DA-BUTSU. That is, when we take refuge (NAMU), Amida Buddha immediately saves us. The two characters NA-MU mean “taking refuge.” “Taking refuge” signifies the mind of sentient beings who abandon the sundry practices and steadfastly entrust themselves to Amida Buddha to save them, [bringing them to Buddhahood] in the afterlife. [The four characters A-MI-DA-BUTSU] express the mind of Amida Tathāgata who, fully knowing sentient beings who entrust themselves-NAMU-we know that the import of the six characters NA-MU-A-MI-DA-BUTSU is precisely that all of us sentient beings are equally saved. Hence our realization of Other-Power faith is itself expressed by the six characters NA-MU-A-MI-DA-BUTSU. We should recognize, therefore, that all the scriptures have the sole intent of bringing us to entrust ourselves to the six characters NA-MU-A-MI-DA-BUTSU.

How is this call different from prayer in Christianity? I don’t mean to make this a discussion about Buddhism versus other religions, except to say that I usually think of the Buddha’s help as wisdom, rather than a supernatural power that responds to our pleas by changing one’s life or circumstances. In Buddhist terms, I’d describe my wife’s experience as first a plea for outside help in changing her situation, perhaps by clearing traffic, shortening her car ride, or easing her breathing. Amida’s appearance was my wife’s realization and acceptance of ultimate reality—whatever happens is due to karmic conditions, not from her own efforts. Coming to this understanding, her mind immediately settled down, although her circumstances had not changed—heavy traffic and a long car ride remained.

Here is what Kaneko says:

The cry of “Buddha, help me” of one in distress issues spontaneously when one comes in direct contact with Other Power. Our cry for help and the Buddha’s promise to save us may seem worlds apart, but that is only when things are seen at a remove, in the way scholars view matters when absorbed in the study of religious concepts. A truly religious sentiment stirs the moment the life of the soul awakens unto itself. This even occurs when the seeker’s cry of “Save me” is in complete rapport with the salvific Buddha’s “I’m coming.” Our call for help is the other side of the loving thoughts the Buddha directs toward us. Rennyo thus spoke constantly of the unity of seeker and Dharma (kihō ittai), and the unity of the Buddha and ordinary beings (butsubon ittai).

Now here’s a story of my own “cry for help.” First some background: In college, the thought first struck me of becoming a Buddhist priest and serving at a temple. After graduation, I studied two years at a Jodo Shinshu school in Kyoto, but after returning home, I gave up. Becoming a minister wasn’t for me, and besides, no way did I understand Pure Land Buddhism. I joked it was “Buddha crazy talk.”

For about 12 years, I worked in various jobs and virtually had no contact with Buddhism, busily focusing on building a career and enjoying life. Then my brother, seven years older, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He asked me to help manage his affairs and I began visiting him periodically in New York City.

His illness progressively worsened until he was forced to enter hospice care. My mother and I traveled to New York to see him. Each day we visited and saw him get sicker and suffer more. He stopped eating. He didn’t recognize us. His stomach swelled so much, he looked pregnant. It was painful to see.

I wondered, “How did all this happen?” I didn’t ask to be there. I’d been enjoying life and now I was pulled into a world of suffering. What could I do to help? What could I do to help myself? I felt helpless. That evening, I returned to my hotel room and, for some reason, got on my knees next to the bed, put my hands together in “gassho,” and recited “Namu Amida Butsu,” over and over again. I hadn’t said nenbutsu in more than 10 years. Why did I say it? I said it as a prayer, as a plea for help… I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

I can’t say I gained any great peace of mind that night. Shortly afterwards, my brother passed away. Looking back, the truth of impermanence had slapped me hard in the face. In that sense, I was confronted with “ultimate reality,” in other words “Other Power,” which went against my desires. The Buddha’s words I studied earlier started making sense. Since then, I returned to the temple, became ordained and made Jodo Shinshu and the study of the Buddha’s teachings the focus of my life.

Kaneko wrote:

Rennyo taught that “with the thought of holding fast to the sleeve of this Buddha Amida, we [should] entrust ourselves [to him] to save us’—words describing a direct encounter [with the Buddha]. Answer our thought of “Buddha, save me” is the Buddha’s immediate assurance, “Count on me to save you.”

In Shinran’s words: For within the one thought-moment of taking refuge—Namu—there is aspiration for birth and directing of virtue. This, then, is the thought that Amida Tathāgata directs to ordinary beings.

Kaneko wrote:

[Rennyo] advocated that the expression of our will to be saved by imploring Amida seen in the words “Buddha, save me,” is concomitant with the expression of the Buddha’s will to save us, seen in “Call on me.” Therefore, Rennyo would say that the Buddha’s saying, “Call on me and surely you will be saved,” is not issued as a condition of salvation, but rather that it is an expression of the Will of that salvific force.

This [intent of the vow] is the summation of the entire life force of the Tathāgata Buddha. When the intent of the vow emerges in the world space of an ordinary being, it takes the form of the single thought of “Save me.” Whether we are speaking of Tathāgata Buddha or ordinary beings, the life force that energizes them is one and the same. When we call on this selfsame life force, the ripples of our pleas reach the other side; when we implore to be saved, the salvific force gushes forth [as if from the very ground on which we stand]. It is here that we have proof that Namu Amidabutsu is nothing other than the unity of seeker and Dharma (kihō ittai).

The summons of the Tathāgata calls to us, its resonance rising up through the depths of the soul to reach the very ground on which we stand. The voice may be so faint as to be barely audible, and though its roots are strong and run deep, it is possible for a person to pay it no heed. On the other hand, it is possible that the summons we want to ignore is a strong one. In that case, we are only deceiving ourselves if we pass our lives turning a deaf ear to that inner call. Or rather, it is because we hear the call of Amida’s summons that we are stricken with remorse that our life full of bad karma makes it impossible to leave off the spurious life we are now living [to start anew].

However, if, hearing that call (monshin), we open ourselves to that summons, this is none other than the emergence of that one thought of imploring the Buddha to save us. It is rare that salvation comes knocking on our door. Yet, this marks the determination of our birth in the Pure Land by the salvific force of the Buddha. This is the proof of our future birth in the midst of our activities in ordinary life (heizei gōjō) and we need not wait in anticipation for the Buddha to appear to us in a vision on our deathbed (raigō).

As a consequence Rennyo taught: The nenbutsu, saying the Name of the Buddha, should then be understood as the nenbutsu of grateful return for Amida’s benevolence, through which the Tathāgata has established our birth. (Letters V. 10)

Recalling the painful memory of my brother deeply saddens me. But now I understand the truth of impermanence and am grateful the Buddha’s teachings are my guide.

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America