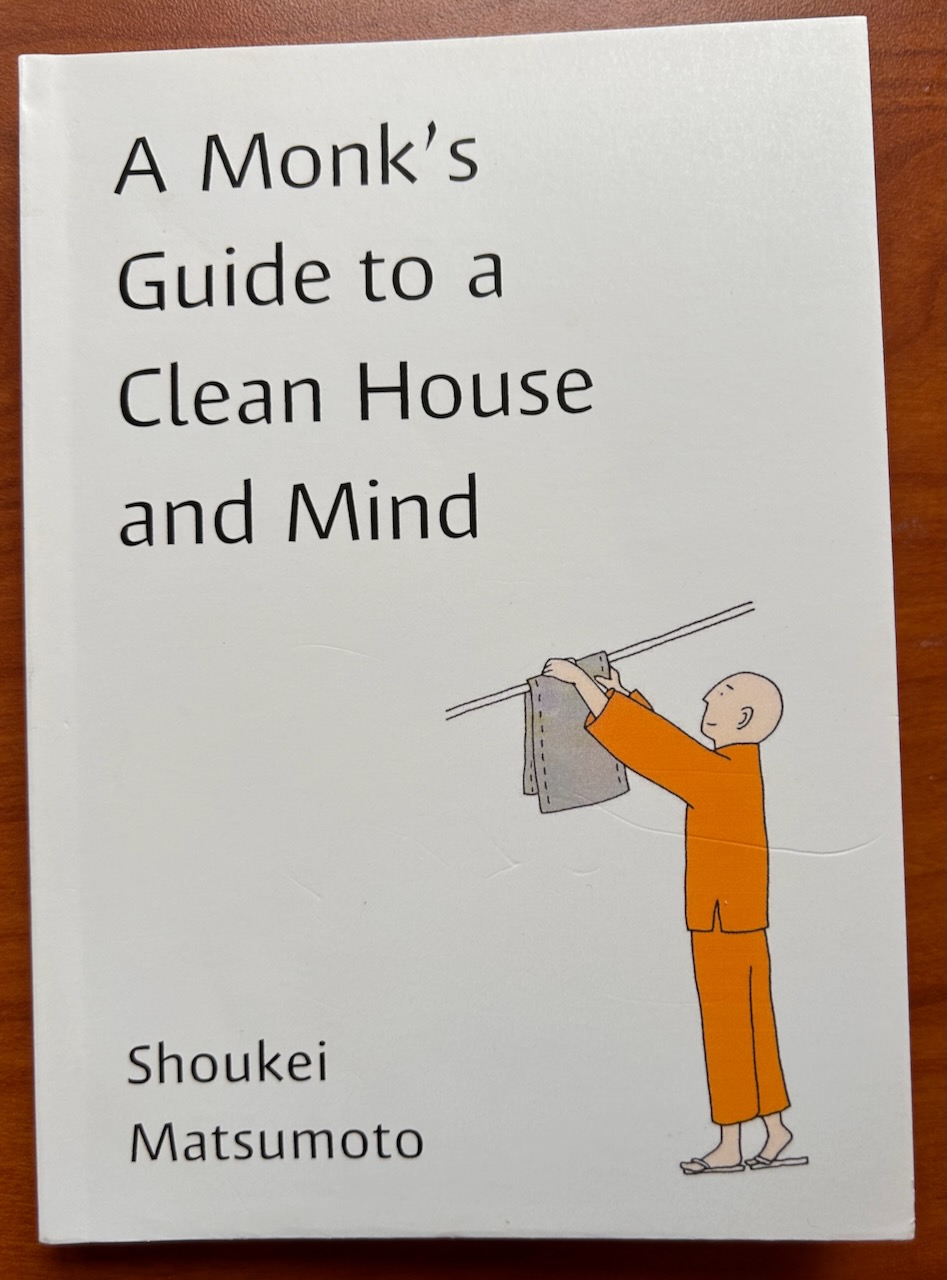

Among his many activities, he started a company, Interbeing, aimed at bringing Buddhist teachings to business people. He earned a Master of Business Administration degree and developed lessons to help priests better run their temples. He organizes spontaneous meet-ups with young people in various cities to discuss life issues. He started a temple café and created a Buddhist website called higan.net. He’s written several books, including the popular “A Monk’s Guide to a Clean House and Mind,” which was translated into 18 languages.

I first met Rev. Matsumoto last Fall at the Jodo Shinshu Center in Berkeley, California, where he spoke on becoming “a good ancestor.” This concept comes from the book “The Good Ancestor, How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World,” by Roman Krznaric, which he liked so much, he translated it into Japanese. I spoke to Rev. Matsumoto recently via Zoom to ask about his activities.

“The role of a Mahayana Buddhist priest is to cultivate people’s sense of ‘inter-beingness,’” Rev. Matsumoto said, “to see the self in a broader realm, going from thinking about ‘myself’ to ‘ourself.” (The term “interbeing” was popularized by Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh to describe the inter-connectedness and interdependence of all things)

The concept of being a “good ancestor” is universal and concerned with long-term thinking, Rev. Matsumoto said. It’s important to ask “How can we become good ancestors to future generations?” In this way, people can start to see their connection to others, to the environment, and to all things, which shape their actions, thoughts and, in the case of business and government, their policies. “This kind of understanding is critical to being good leaders in the corporate world, in government, wherever,” Rev. Matsumoto said.

When he was young, he often visited his grandfather’s Higashi Honganji temple in Hokkaido, Japan. He attended services such as Hoonko, and also lectures by visiting dharma teachers but wondered how they could talk about a Pure Land in the West. “It sounded very superstitious to me,” he said.

Yet he was curious. Sparking his interest was a certain personal anxiety. “I had a big fear of death,” Rev. Matsumoto said. “At the end of our lives, we need to say goodbye to everyone and everything and leave this world. If I am destined to die in the end, how can I live?”

At Tokyo University, he majored in Western philosophy. After graduation, he was introduced by a friend to Nishi Honganji’s Komyoji temple in Tokyo, through which he eventually became ordained. However, he wanted to pursue a route beyond the traditional temple role, instead focusing on people outside the temple organization who normally had no contact with Buddhism. “I wanted to be a bridge between the shaba world (realm of suffering) and Buddha’s world (realm of enlightenment).”

Although he had become familiar with words and concepts of Buddhism, he wanted to learn more about business and a more worldly way of thinking. He decided to attend school in India, which also allowed him to achieve his dream of living in that country as a Buddhist priest. He returned to Japan with an MBA degree and started a school called “Mirai no Jūshoku no Juku” (temple management school for priests). Today the school is 12 years old and has more than 800 alumni priests.

After conveying business ideas to the Buddhist community, Matsumoto flipped his focused by aiming to bring Buddhist concepts to the business and government community through a new company Interbeing. The company offers one-on-one sessions with executives and leaders to help them see their connection to the greater world and future generations, which encourages long-term planning and a greater awareness of, for example, the importance of ecology, social welfare and corporate responsibility.

“I feel it’s easy to get interest from business people, especially top leaders,” Rev. Matsumoto said. “There’s a trend in business called ‘purpose-driven management.’ Young and talented people in business today tend to be less interested in making money and more interested in pursuing meaningful purpose through business.”

Perhaps his broadest influence comes from his books. He’s written five books in Japanese, two of which have been published in English. “A Monk’s Guide to a Clean House and Mind” was translated into 18 languages, including French, German, Italian, Korean, Mongolian and Hebrew. This book struck me as a “Marie Kondo” like easy-to-read guide that offered practical tips and nuggets of general Buddhist wisdom. It changed my thinking about cleaning, from a dreaded chore to a form of spiritual practice and meditation. After all, Buddhist monks spend much time cleaning temples and monasteries, an activity considered essential and important, and also a form of practice. Thus while cleaning, they wear their robes.

Rev. Matsumoto wrote:

If you ever have the chance, observe how monks clean their temple grounds. Dressed in samue robes, the traditional work wear of Buddhist monks, they’ll be silently engaged in their designated chores and appear cheerful and well. Cleaning isn’t considered burdensome or something you don’t really want to do and wish to get over with as soon as possible. They say that one of the Buddha’s disciples achieved enlightenment doing nothing but sweeping while chanting, “Clean off dust. Remove grime.” Cleaning is carried out not because there is dirt but because it’s an ascetic practice to cultivate the mind.

Another book, “A Quiet Mind, Buddhist Ways to Calm the Noise in Your Head,” offers practical advice about everyday living, such as how to think about relationships, money, personal desires, watching TV and using the Internet in relation to Buddhist teachings. Again, it’s written in an easy-to-digest gentle style.

Rev. Matsumoto wrote:

For better or worse, we happen to exist in an age where we lead very hectic lives.

With the development of various information and social media channels through the internet, the range of personal relationships and news that each person gets caught up in has dramatically expanded. There’s so much new information and not enough time to organize it all, so we spend each day being busy.

Personally, I believe this is a rather dangerous situation. Through various experiences, human beings should be able to understand the world and steadily grow by calming the mind and considering things carefully. However, if we can’t find any quiet time away from the noise, then we won’t have the space to grow.

Even if we process a lot of information during our lives, no matter how long we live for, it will all come to nothing if we can’t digest that information and learn from it.

We must look at ourselves and the things around us with a calm and peaceful mind, especially in this noisy age. It’s important that we deepen our “awareness” of the reality of the world and of ourselves.

I found that messages in these books expressed basic teachings and general Buddhism, but lacked perspective from Jodo Shinshu and Shinran Shonin’s teachings. So I asked Rev. Matsumoto about it.

He said he has increasingly come to appreciate Shinran Shonin’s teachings, especially his humbleness and acknowledgement of one’s shortcomings and ignorance. Like Shinran, Rev. Matsumoto said, “we are fools, we don’t know everything, and we should be humble.”

Rev. Matsumoto recently finished writing another book, soon to be published, which he described as a conversation between a Buddhist monk and a business person in a mountain temple. The monk sometimes speaks like Shinran, sometimes like Honen, sometimes like other teachers, and sometimes like Matsumoto himself.

In response to the question, “How can we be a good ancestor for the future generation,” he quotes Audrey Tang Feng, Taiwan’s former digital minister, who said it means “leaving more options for future generations.” The danger of actions taken by those who think they know better may result in narrowing options for the future.

If we understand we don’t know everything, that in fact, we are ignorant of many things, then we can be humble in approaching the future, Rev. Matsumoto said. That means ensuring future generations have the freedom to choose, which he said, is how we can be a good ancestor.

-Rev. Ken Yamada, editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America