By Rev. Patti Nakai

One day Rev. Gyoko Saito filled in to lead a study class at the Buddhist Temple of Chicago. Instead of showering us with knowledge about Buddhist history and concepts, Rev. Saito spoke not to our heads but aimed for our guts.

When I joined the Buddhist Temple of Chicago in the late 1970s, I felt a personal closeness to the resident minister, Rev. Gyomay Kubose. I attended his weekly study class and the Sunday morning meditation that he led. At that time the meditation group was very tight-knit and we had social gatherings where we got to be with Rev. Kubose in a relaxed setting. On my days off from my banking job, I would hang out at the temple and visit with Rev. Kubose and from time to time he and his wife Minnie would invite me to their apartment for dinner.

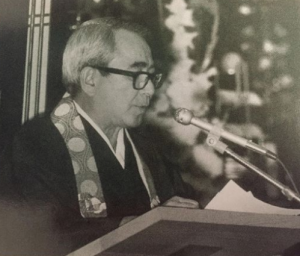

So while I felt close to Rev. Kubose, Rev. Saito was a distant figure to me. I thought some of his Dharma talks were interesting, but he seemed to speak as a “pedestrian,” just another man on the street, not from the lofty heights of transcendent wisdom as Rev. Kubose did.

Back then in that study class, Rev. Saito asked us, “What is your highest wish?” Paraphrasing Soren Kierkegaard, he said, “If you have ordinary wishes, there are no problems, but if you have the highest wish, the problem of living arises.” In my case at the time, I felt I had lots of problems, but I realized those problems coming from my “ordinary wishes” couldn’t be the problem of life that Rev. Saito said Kierkegaard and Shinran struggled with. To know that wish that comes from beyond our selfish material desires, Rev. Saito said it was important to encounter the teacher who attacks our shallow egoistical view of ourselves and awakens us to the path leading to the discovery of who we really are.

There is the Buddhism that makes us feel comfortable when we hear phrases like “come as you are” and “everyday suchness.” But at that study class, Rev. Saito reminded me that there is the Buddhism that is about earnest seeking and not plopping down into a complacent state. It is the Buddhism that kicks us out of the bubble of associating only with people similar to us and makes us discover the magnificence of lives very different from ours. That is the Buddhism of hongan, what Rev. Saito and Dr. Nobuo Haneda translated as “innermost aspiration” instead of using the misleading term “Original Vow.” That deep wish to awaken to the oneness of life is in each life – it’s not some particular “vow” (promise) originating with a specific being, as thought by those who read the Larger Sutra too literally.

More than that new way of translating hongan into English, Rev. Saito translated the “innermost aspiration” with his whole life. Remembering the talks he gave in Chicago and Los Angeles and reading his articles, I see how he identified with a wide variety of lives, not judging anyone as separate and inferior to himself. He could reverberate with the courageous dedication of Martin Luther King, Jr. and see himself in the scam artist walking down Broadway or the disturbed woman shouting on Leland Avenue. Animals and children were his teachers and like his main teacher, Akegarasu Haya, Rev. Saito learned from the great thinkers of diverse cultures and religions, not just Asian Buddhists.

Rev. Saito could have lived his life satisfying his “ordinary wishes” by continuing his studies to be an electrical engineer. Instead, inspired by Akegarasu, he entered the Buddhist ministry. In Chicago, the members really wanted a minister who helped people feel good about identifying as Buddhist mixed in with pride and appreciation of Japanese culture. But Rev. Saito failed to be that kind of minister and instead strove to make each of us aware of the “highest wish” that goes beyond a Buddhist or Japanese identity. He did this in his talks, writings and most poignantly by example.

In this month of March for Founder’s Day, we will sing the praises of Rev. Kubose who is a significant figure in bringing Jodo Shinshu to English-speaking audiences as well as being important as our temple’s founding minister. But in March is also the observance of Koshu-ki, the memorial of Rev. Saito. Maybe if for no one else but me, it’s an occasion to reflect on how Rev. Saito is the true teacher by showing me how to be the true student of life, to open up and let go of my self-serving tribal views.

*****

From “The True Birthplace of Humanity” by Rev. Gyoko Saito

[I like this excerpt because it shows Rev. Saito’s joy at learning from other people – such as this account about Nigerian people – PN]

Last night for our gathering of young Buddhist groups we had a guest speaker who had majored in educational psychology. He talked about his experiences while he was in Nigeria for two years as a member of the Peace Corps. “When we Americans think of Nigeria from the United States, then Nigeria is a very backward and culturally undeveloped country, and there is nothing to learn from it. But when I went there I learned the most important thing in my life. One day I went to buy flowers at the market. I asked, ‘May I buy these flowers?’ The Nigerian said, ‘Hello.’ So I asked him again, ‘May I buy these flowers?’ For a second time he said to me, ‘Hello.’ When I asked him a third time, I got back a thunderous answer, ‘HELLO!’ Then I remembered the Nigerian custom that even when we buy something, first we have to exchange ‘Hello’ with each other, that is, we have to communicate with each other as human beings. Then business can follow. I had forgotten the custom completely.”

When we think from the United States, we think of Nigeria as a backward country, but according to this man, the most important human teaching, that is, the dialogue of human beings, is there, strong, in Nigeria. When I realized this, then I thought to myself, the real native country of our life is the country where we have true dialogue between human beings. That is the true native country of humanity.