By Rev. Patti Nakai

(This article was originally published in Buddhist Temple of Chicago’s Bulletin, August 1997)

It may sound paradoxical, but throughout Buddhism’s history, teachers who spoke most powerfully to people of their generation and to generations afterward looked backward in time to India and heard Shakamuni Buddha’s words directly as possible. They broke through layers of stale traditions and customs separating the Buddha’s time and their own.

Buddhist master Nāgārjuna’s (2nd century CE) name means “Dragon’s Lair” because for him, rediscovering Shakamuni’s teachings was like fighting through a cave of fire-breathing rule-sticklers and strict imitators of Shakamuni’s outward lifestyle. In bringing out the jewel of the teachings for the world to encounter (Mahāyāna, “large vehicle”), he needed to get past narrow-minded monks who’d keep the teachings only for themselves (Hīnayāna, “small vehicle”).

Haya Akegarasu (1877-1954) might have been just another priest mired in a stagnant tradition smothering Japanese Buddhism’s spirit if not for a fortuitous encounter. He was born into a temple family where the priesthood was typically handed down from father-to-son (unlike the original Buddhist tradition of celibate masters passing the mantle to their disciples). Unfortunately for the Akegarasu family, Haya’s father died when the boy was ten years old. Although his mother succeeded in her struggle to raise him by herself, she didn’t serve as an indoctrinator as much as a father would have. Young Haya grew up without fixed ideas of how a priest should be. He hoped to become a diplomat rather than a priest. However, his encounter with Manshi Kiyozawa (1863-1903), his high school English teacher, changed the course of his life.

For Kiyozawa, an outsider to the traditional temple system, Buddhism was a personal path of seeking true peace of mind, not a career of carrying on a family business chanting for memorial services. While generations of Jōdo Shinshū priests in Japan were educated on nitpicky analyses of commentaries, Kiyozawa found it more meaningful listening directly from Shinran in the Tannishō. For Akegarasu and other Shinshu followers, hearing Shinran’s words—in what had been a little-known text kept from mass circulation for hundreds of years—was a revelation.

After Kiyozawa’s death, Akegarasu carried on his teacher’s mission to make Shinshu more understandable to modern people by introducing them to the Tannishō, in which Shinran speaks plainly without complicated metaphysics and philosophy. On the wave of this Tannishō rediscovery, Akegarasu became a popular and highly respected priest.

In 1925, a scandal destroyed Akegarasu’s reputation, and he retreated to his family’s temple near Kanazawa. He described his despair at the time as being so great, he almost committed suicide. Caring for his mother was the only thing keeping him alive. The Tannishō no longer had the power to comfort him, but instead of giving up on Shinran, Akegarasu was driven to find Shinran’s source of inspiration. He embarked on an intense study of the Eternal Life Sutra (The Larger Sukhāvatīvyūha Sutra), which Shinran clearly stated in his writings was the basis of his conviction and practice.

At that point, Akegarasu felt his life touched bottom and he was unable to raise himself up. In the Eternal Life Sutra, he heard a powerful shout coming deep from the Buddha’s heart, or rather, from Shakamuni’s mouth. It was the shout of his own being. It was the shout of one life realizing the unique workings of all Life itself.

In the Eternal Life Sutra, Shakamuni tells the story of a prototypical seeker, Dharmakara, who finds true enlightenment when all feelings of superiority and separation are broken down inside him. His name becomes “the one who bows down (Namu) to all of life (Amida) as enlightened beings (Butsu).” Shakamuni explained by calling the name of this seeker, “Namu Amida Butsu,” we are reminded of the ultimate goal of our searching and yearning, our thoughts, and efforts.

By going back in time to receive the Nembutsu teachings directly from Shakamuni, Akegarasu was inspired to the degree of feeling he had died and was reborn. He broke free of personal scandal, centuries of feudal traditions, all labels, categories, and fixed concepts which haunted him, as he ventured back into the world to express the fervor of his spiritual seeking and joy of living the path of Oneness

It seems Akegarasu wanted his essay about Shinran and the Eternal Life Sutra translated into English (included in the 1936 book Selections From the Nippon Seishin Library) because when he encountered second-generation Japanese-American Nisei and their friends on the U.S. mainland and Hawaii, he found that misleading notions about Pure Land Buddhism from feudal Japan were brought to America.

In the past, Shinshu encouraged barely literate peasants to take their lives seriously, so the ruling class considered the teachings subversive, blaming them for peasant uprisings after Shinran’s time. The Tokugawa regime (1603- 1868) enforced the message that priests should preach passivity, that peasants be satisfied with their meager lot, and they should look forward to pleasures of paradise after they die. Not only common people, but priests themselves were kept ignorant of much of basic Buddhist scriptures, so these twisted Pure Land ideas were passed down to generations who knew little of what sutras actually meant.

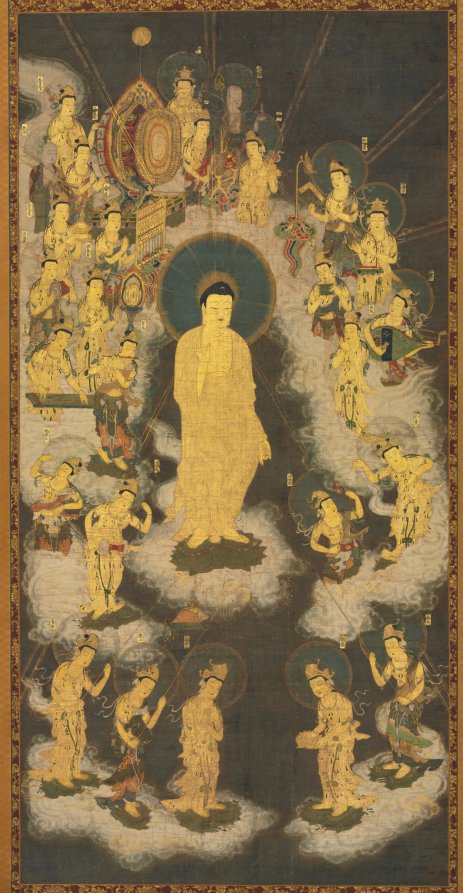

In his essay, Akegarasu indicated that Shakamuni appeared in the Eternal Life Sutra at a great turning point. In the sutra, the Great Teacher drops the stern schoolmaster expression of one who feels he has important instructions to give to ignorant hordes before him. Instead, Shakamuni’s face glows with enjoyment, like someone having a lively conversation with a dear friend, free of inhibitions and worries. Seeing this, disciple Ananda felt compelled to comment, “I have been serving you for many years, but I never observed your appearance so brightly shining in ecstasy as today.”

Ananda asks if the Buddha is contemplating other Buddhas and being contemplated by them. However, Shakamuni doesn’t see invisible Buddhas floating in space. Instead, his eyes have opened to wonderful faces of enlightenment all around him – monks and lay people, young and old, rich and poor, men and women. To express this sublime state of Oneness in his mind, Shakamuni tells the story of Dharmakara.

Usually, Buddhists point to enlightenment under the Bodhi tree as Shakamuni’s great life event. Shinran learned from Pure Land teachers before him the Eternal Life Sutra depicts a significant deepening of Shakamuni’s enlightenment. This shift in perspective from being a teacher facing students to becoming an integral part of a landscape of shining faces is what may be called “birth in the Pure Land.”

For members of the Buddhist Temple of Chicago, it’s probably not surprising to hear Pure Land defined as realizing the world of Oneness here and now. Chicago minister Rev. Gyomay Kubose (1905-2000) was Akegarasu’s student. By looking at Akegarasu’s life and his study of the Eternal Life Sutra, we see that attaining this state of Pure Land isn’t easy. As Shinran tells us, it involves continual learning (kyō), practice (gyō), and commitment (shin) because our egoistic way of relating to the world is so entrenched. The ego is like a hard shell that keeps growing back, so Akegarasu said we must continually break out of it.

There are many teachings and practices that can be followed in this constant endeavor to realize Oneness, but in the Eternal Life Sutra, we’re told how reciting the name, “Namu Amida Butsu,” works as a powerful reminder of the Pure Land we actually live in, and of the blinders of ego keeping us from seeing clearly.

When we pay our respects to Haya Akegarasu at Kosoki (his memorial day), I hope we all seek to hear the Shout of Buddha for ourselves and not settle for anyone’s second-hand description.

-Rev. Nakai served as resident minister of Chicago Buddhist Temple