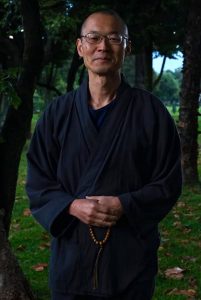

Rev. Miki Nakura exudes the peaceful bearing one expects of a Buddhist priest. He closes his eyes, ponders a question, and answers slowly with a slight Japanese accent. Every day, he meditates. Such calmness belies a personal history beset by tragedy, dashed dreams and a deep resentment against his mother. At one time, he thought, my mother is “my enemy.”

But something happened. Now, Rev. Nakura leads the Jodo-Shinshu Shin-Buddhist New York Sangha, giving dharma talks, meeting with members and sharing the Jodo Shinshu teachings. He also teaches meditation, leading weekly sessions online, which have attracted participants from other states and outside the country. After toiling as a company worker and a circuitous search for purpose, his life now is devoted to helping others.

How did this transformation take place?

Born in 1962, his home life in Osaka was happy enough. His father, a fairly Japanese typical businessman, liked to drink, gamble and play golf. His mother cared for home and his younger brother. As a not-so-serious college student, he preferred playing football. Then, his father was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, suddenly casting a dark shadow over the family. But Nakura had plans to graduate, find a job at a major company and leave home for the big city of Tokyo.

A year later, his father died. His mother was devastated. Her mother also had passed away a year earlier. Nakura continued his job search. An offer came from Nippon Steel in Tokyo—a dream job. His mother pleaded with him not to go. So did his brother. His mother began acting strange, pleading, yelling, begging, as if she’d gone insane.

He told her, this is my chance to fulfill my dream! They argued constantly. As he prepared to leave, she ran to the front door, and poured gasoline over her head, intending to light herself on fire. This crazy woman, standing in the way of my dreams!

He felt no choice but to stay home. His father’s friend arranged a job at a large Japanese bank. He began working, commuting from home, but he resented it. He resented living at home. He resented his job. He resented his life. Foremost, he resented his mother for ruining his life. His head filled with thoughts of “my mother is my enemy.” He was miserable.

Knowing his troubles, a friend introduced him to a kind, elderly woman, Tatsuko Kato, who always seemed to offer good advice. He told her his troubles. She said, “Human life is filled with suffering.” Now he was experiencing it. She had found solace in the Buddhist teachings. She had a “brilliant countenance and soft voice.” He felt compassion from her. She told him to talk to her anytime.

He never before felt such inner turmoil. She introduced him to Rev. Norimasa Hachiya, a Buddhist priest at a Higashi Honganji temple in Osaka. He began attending services and dharma talks. For the first time, he heard the words “Pure Land,” “Amida Buddha,” “salvation,” and others, but didn’t understand them. Yet, he felt something genuine. He continued going.

He also began practicing seated meditation, although not the strict Zen Buddhist kind—sitting-in-lotus position, rigid straight back, arms-bowed, hands-forming-a-circle-style. He sat “seiza,” Japanese style, with legs folded under buttocks, body upright but not rigid, hands folded gently together, eyes closed. Torajiro Okada popularized this easier, more accessible way of meditation in the early 20th century. Both Mrs. Kato and Rev. Hachiya meditated this way.

He wanted to resolve his personal problems, especially with his mother. But how? During those years he worked at the company in the 1990s, Japan’s economy boomed, driven by the country’s mass consumerism. Banks were seemingly front and center, a world from which he felt disconnected. He hated it.

One day, as he repeated his troubles and complaints to Mrs. Kato, she suddenly blurted out: “You think you’re a righteous man. You always criticize your mother, your job, your company, and even Japan’s economy. You’re always looking down at others. This is wrong! Look at yourself! Buddhism is about constantly looking at yourself.”

Nakura was shocked. He always felt the cause of his suffering was outside himself. He thought for certain, “If my mother wasn’t there, I’d be happy.” He always thought she was unreasonable—in fact, beyond unreasonable. She was wrong to crush his dreams. She was the “enemy.”

He began thinking about her situation and her feelings. He began realizing how lonely she must have felt. She had lost her mother, lost her husband, and now, she was about to lose her son. He couldn’t see her suffering. Suddenly the thought hit him: “How shallow I am—always telling others about my own unhappiness.” He realized: The cause of suffering was within himself.

With this change in perspective, his relationship with his mother improved and they became closer. His resentment disappeared, replaced with feelings of shame and humbleness, with understanding, and with a newfound respect and love for his mother.

The problem now was what to do with his life. He hated his office job. He thought fondly of his visits to Rev. Hachiya and how he always warmly greeted him, served him tea, and quietly listened with compassion. Nakura thought, I’d like to become a minister like that and help people. Rev. Hachiya opposed the idea. Before you start saving others, he said, you must save yourself. Also, one needn’t be a priest to help people. Numerous commoners in the Shinshu tradition, such as Saichi and Genza, shared their experiences with others without becoming priests.

After 12 years at the bank, Nakura quit. He traveled to India and visited Bodhgaya, the site where the Buddha was enlightened. After returning, he couldn’t decide what to do and languished at home. Two years passed and he hit rock bottom. He was 38 years old.

Again he visited Rev. Hachiya, who told him, “Whatever job you think you can do, just do it.” Somehow, he felt liberated. Yes, he could do any job. His family too encouraged him to move out and become independent.

He browsed employment listings. He became a door-to-door salesman selling telephone service. He worked in an office. He lived in a Japanese Inn, doing odd jobs. He lived in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka. Wherever he was, he attended Buddhist lectures and seminars. In five years, he cycled through 10 jobs. He also began leading meditation classes and teaching classes on Buddhism.

In his heart, he wanted to become a Buddhist priest. Rev. Hachiya finally agreed. He became an ordained priest with Higashi Honganji at age 43, which he points out, is the same age that Rennyo Shonin (“the second founder of Jodo Shinshu”) became abbot. He was assigned to Higashi Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii in Honolulu, where for four years, he served as resident minister, conducting services, meeting members, teaching classes and maintaining the temple grounds.

He still dreamed of the big city. In 2012, he moved to New York City to continue his Jodo Shinshu activities. He formed the Jodo-Shinshu Shin-Buddhist New York Sangha, which began meeting in a Japanese restaurant and a Zen temple before the pandemic. He continues his activities online, especially his meditation sessions.

His journey continues.

(Rev. Nakura welcomes anyone to join his free online meditation sessions, every Tuesday and Saturday at 12:30 p.m. (Eastern Time). Wherever you live, you can join. Contact him at: mikinakura87@gmail.com

-Rev. Ken Yamada, editor at Shinshu Center of America