Although considered the “second founder” of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, Rennyo Shonin shaped foremost how Shinshu is practiced today. Moreover, living in a turbulent era of civil unrest, religious persecution, and social upheaval, he literally saved the Honganji temple from the flames of war and conflict.

Shinshu’s “first” founder Shinran Shonin famously declared he had no disciples and had not started a new Buddhist denomination. Only later did his descendants establish a temple devoted to his teachings. A hundred and fifty years later, Rennyo (1415-1499) withstood violent attacks and persecution and built the temple into a major religious institution.

Today, the “how” and “where” Shinshu is practiced are thanks largely to Rennyo. Our temples exist because of the organizational foundation he laid 600 years ago. He started the tradition of chanting “Shoshinge,” Shinran’s verses summarizing Pure Land teachings. He stressed the importance of Hoonko services (Shinran’s memorial). His letter “White Ashes” is traditionally read at funerals and memorials. We recite “Namu Amida Butsu” because Rennyo chose that six-character phrase over other Nembutsu expressions used by Shinran.

A blood descendant of Shinran, Rennyo was born in Kyoto at the Honganji temple, which had fallen on hard times and disrepair. He became the temple’s eighth abbot. Charismatic and personable, he began growing the sangha and temple’s economic base, which incurred the wrath of the older Japanese temples. In 1465, Mt. Hiei’s warrior monks marched to Kyoto and burned down Honganji, forcing Rennyo to flee for his life.

Eventually Rennyo moved to Japan’s eastern seaboard and established a temple at Yoshizaki (present day Fukui prefecture). There, Jodo Shinshu spread throughout the countryside, where even today, Shinshu remains a dominant presence.

In Yoshizaki , Rennyo faced continuing threats, persecution, and attacks. The temple was built like a fortress, protected by an armed militia called Ikko ikki (“single faith folllowers”). Ikko Ikki would later rise up against the local provincial governor, whom they saw as unjust and oppressive, seizing power and becoming the only district controlled by commoners.

Amid such turmoil, Rennyo needed to address societal concerns, in addition to propagating spiritual teachings. For example in a letter, he wrote:

(Shinran) also carefully stipulated that we should observe (the principles of) humanity, justice, propriety, wisdom, and sincerity; that we should honor the laws of the state; and that, deep within, we should take Other-Power faith established by the Primal Vow as fundamental.

Although Shinran never established “rules of conduct” for followers, Rennyo felt compelled to create some. Among them: Do not slander other religions; do not denigrate the various gods and buddhas; and be fully obedient to provincial military governors and local land stewards.

Living in such turbulent times, Rennyo was forced to balance spiritual guidance with rules for living in society. To spread the teachings, he wrote numerous letters, totaling 158, explaining doctrine, dispensing advice, and correcting wrong views. His most famous letter, “White Ashes,” implores us to reflect on life’s impermanence:

The people we leave behind and the people who go before us, are more numerous than dewdrops that rest briefly on leaves and branches. Hence, I may have a radiant face in the morning, but in the evening, become no more than white ashes.

In a definitive book on Rennyo’s life, “Rennyo: The Second Founder of Shin Buddhism,” Minor L. Rogers and Ann T. Rogers wrote:

Rennyo’s dilemma as the leader of an institution increasingly vulnerable to politically-motivated nenbutsu devotees comes into sharper focus. On the one hand, he sought to be faithful to Shinran’s teachings, for the most part apolitical, and on the other, to be responsive to the legitimate aspirations of his followers for spiritual nurture and some degree of security amidst political and social instability.

In 1478, Rennyo moved the main Honganji temple closer to Kyoto, eventually settling in what is now present-day Osaka, currently the site of Osaka castle. He led the building of Ishiyama Honganji in an area bordered by rivers, which provided natural defensive boundaries. There, some 70 years later, Honganji defended by Ikko Ikki and allies, fought warlord Oda Nobunaga to a stalemate in a 10-year war. After a truce was signed, Honganji subsequently split into two—called Higashi Honganji and Nishi Honganji—both located in Kyoto.

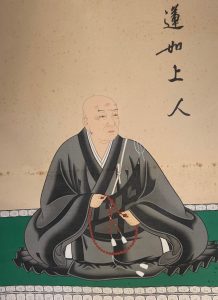

Rennyo passed away at age 85. At some Higashi Honganji temples, Rennyo’s memorial service is held monthly on the 25th day. His image on a scroll hangs on the left side of the altar. On the right is Shinran’s image.

Rennyo fought to preserve and strengthen the temple organization because he felt it was the best place for hearing Shinran’s teachings, for coming together as a Sangha, for realizing a sense of shared spirituality, and for deepening one’s faith. Really thanks to Rennyo, our temples exist today.

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America