By Rev. Ken Yamada

People sometimes receive a valuable inheritance from their Buddhist parents or grandparents, but don’t realize its value. So they donate it to the temple.

Buddhist home altars, commonly called “butsudan” in Japanese (or the preferred term “onaibutsu”), if purchased new today in Japan cost hundreds, and sometimes, thousands of dollars. But their real value is spiritual.

Let’s discuss the meaning of home altars and how best to use them, particularly in Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. First some background information.

In Japan today, there’s a disturbing trend of people discarding home altars, so much so, some companies specialize in altar disposals. Inherited by adult children, they feel altars embody their ancestors’ spirits and so disposal must be done properly, often involving rituals by priests, cremation and even burial. If not done right, they may feel cursed or think they’ll suffer bad luck.

Perhaps here people share similar feelings, so they bring unwanted onaibutsu to temples. Of course, there’s hope someone could better use and appreciate them.

As a Buddhist, I think it’s unfortunate people don’t understand the spiritual value of home altars. Knowing so would help them appreciate and treat them as family treasures. Perhaps because they just can’t throw it away means deep inside they know it’s something special. That feeling could be a starting point.

Stories abound about how before a home altar, grandmas and grandpas devoutly “prayed” daily, or how others spoke to a deceased spouse or child. Perhaps it’s superstition or perhaps it’s a way people transcend time to connect with loved ones. Understanding the function and symbolism of home altars I think helps put these stories in perspective.

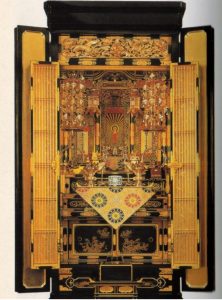

The following are basic, essential elements of a home altar. The container typically is a wooden box with doors. Sizes range anywhere from a small shoebox to a closet-size refrigerator (common in some rural areas of Japan).

The centerpiece is most important, consisting of one of the following: a statue of Amida Buddha, a scroll with an image of Amida Buddha, or a scroll with Chinese characters of the name Amida Buddha (Namu Amida Butsu).

In front on the left is a vase for flowers. On the right is a candle in a holder. In the middle is a bowl for incense. Usually there’s a small bell and stick for ringing it.

Home altars can be more elaborate, containing scrolls of Shinran Shonin, Rennyo Shonin, variations of Amida Buddha’s name, or images of other Buddhist teachers. There may be more flowers and candles, memorial tablets, food offerings, embroidered cloth, and outside the altar, pictures of deceased loved ones.

For now, let’s focus on essentials. It doesn’t matter if the centerpiece is a statue or scroll, or whether there’s an Amida Buddha image or name. All symbolize Great Truth, meaning wisdom that liberates our mind. This central worship object gives us a way to focus on the ultimate Truth of life—who we are and the meaning of our life.

The candle represents wisdom. Candles radiate light, which allows us to see through darkness, meaning our ignorance. Flowers represent life and symbolize compassion. Flowers cannot grow without help from the sun, rain, wind and earth. In this way, we’re reminded we cannot live without depending on other people and things. Flowers also represent impermanence, the constantly changing and dynamic nature of the universe. Changing flowers that have wilted and browned is a good reminder of impermanence.

Incense represents Oneness of life and death because as it burns, it lives, meaning it both lives and dies at the same time. Offering incense is an expression of appreciation for Truth that liberates us, and also for lives to which we are connected, including people from the past and present.

Standard practice before a home altar consists of ensuring fresh flowers, offering rice, lighting a candle, burning incense and chanting a Buddhist sutra. However, you need not do all of these things. You can simply put your hands together, recite “Namu Amida Butsu,” and bow. These words symbolize great Truth and remind us to live with this big picture view of Life.

The home altar also is a place for observing special occasions, such as the death of a loved one, certain anniversary date memorials, the birth of a baby, recovery from illness, a visit from a friend, or any special day. It’s a place to reflect daily on life and to express our appreciation. Starting the day before the home altar makes any day special.

Many people discover the value of home altars when experiencing the death of a loved one. Suddenly, the home altar becomes a special place to honor that person, to express gratitude for that person’s life, and perhaps even to communicate with that person, understanding karma that bind us together.

If you have a home altar, please don’t throw it away or keep it stored away and hidden. If you don’t have one, I encourage you to get one. It needn’t be fancy or expensive. You also can make your own by merely assembling the essential pieces. Please use it and make it part of your everyday life.

Pausing daily before the home altar, performing little rituals, however small and short, help provide grounding for everyday life and remind us to follow a path of self-reflection. It is calming before a hectic day and calming after a stressful day. By doing so, that little altar becomes a special place to discover what’s truly priceless—wisdom, understanding, tranquility, and gratitude.

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America