By Rev. Patti Nakai

“What the heck,” a newcomer may wonder after hearing a common explanation of Jodo Shinshu. The explanation? “Just recite Namo Amida Butsu and rebirth after death is guaranteed in a bejeweled paradise called Pure Land.”

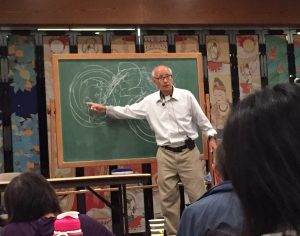

That message heard for decades at North American temples is what Maida Center of Buddhism director Nobuo Haneda called “Hybrid Shinshu,” as opposed to “Shinran’s Shinshu.” During a July retreat in Berkeley California, Dr. Haneda spoke in detail about how the Shin Buddhism presented in the West deviates significantly from the true essence (shin-shū) of the Buddhist teachings Shinran conveyed.

Dr. Haneda prefaced his presentation by calling it a work-in-progress and very much incomplete. However he offered many thought-provoking points, which I think will help us understand the true Jodo Shinshu that Shinran meant, rather than an often “hybrid” or misleading form taught today. My apologies to Dr. Haneda for any errors or omissions in my summary, but hopefully you’ll find value in it nevertheless.

To clarify this true essence, Shinran described his own spiritual journey as the “three vow transition” (san-gan ten-nyū). The first phase refers to when Shinran lived as a monastic, believing rigorous practices could eliminate defilements from his heart and mind. This is a common Buddhist belief, especially in the West, whereas a person can become “good” through practices such as meditation and austere living.

Failing as a monastic, Shinran became a follower of Honen, who came to be known as founder of the Jodo-shu Pure Land sect, derived from teachings evolved from Central and Eastern Asia, which gave laypeople hope in teaching recitation of Amida Buddha’s name as means to a Pure Land afterlife and ultimately enlightenment. The basis for this second phase is a popular idea in many religions—that people are “saved” after death through faith in an external power.

After spending time in this kind of Jodo-shu group, Shinran doubted this approach. Like the monastic path, Shinran still felt the ego’s pull, thinking “I’ve got to do this, then I’ll earn my reward.” This thinking didn’t jibe with Mahayana Buddhist teachings of transcending self-attachment and identifying with all beings.

Through discussions with Honen and by studying the Larger Sutra, Shinran entered a third phase where ultimately his shell of self-attachment was shattered and he was liberated into the flow of universal life, which was a realm of non-dualistic wisdom symbolized as Pure Land. This was the exact experience that Shakyamuni Buddha described in the story of bodhisattva Dharmakara, told in the Larger Sutra, which is why it resonated deeply with Shinran.

This third stage is expressed as a joyful shout of liberation that permeates Shinran’s writings, such as the Kyogyoshinsho. But after Shinran’s death, that shout was muzzled by his own descendants – namely Kakunyo (1270-1351), Zonkaku (1290-1373) and Rennyo (1415-1499).

Those three teachers, who all were abbots of Honganji, instead emphasized aspects of Jodo-shu teachings—Shinran’s second phase—not his ultimate liberation and realization of Jodo Shinshu teachings. They directed people’s attention to a future world of personal reward in an afterlife, instead of appreciating the present life, which Shinran emphasized.

Shinran’s view transcended judgments of “good” and “bad,” which are based on what’s advantageous or not to the self. A person free from the bonds of self-interest feels little obligation to obey authorities. By contrast, Kakunyo, Zonkaku and Rennyo were concerned with building the Honganji temple organization and with gaining government support. Fostering independent thinking wasn’t a priority.

Practically, it was best to keep the vocal, radical Shinran out of sight, and instead, promote a Shinran as quiet miracle-worker. For centuries afterwards, lay followers mainly heard the letters of Rennyo and did not have access to Shinran’s actual words, which added to misinterpretation. Access to Shinran’s words still is a problem today in the West due to inaccurate English translations of Japanese writings.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), Shinshu was further diluted by the Tokugawa government’s insistence on Shin Buddhist priests performing elaborate rituals and doing hair-splitting doctrinal studies.

In late 1800s, the beginning of Japan’s modern era, laypeople finally could see Shinran as a dynamic human being and could hear his voice. The restorers of Shinran’s Shinshu were primarily Higashi Honganji teachers, according to Dr. Haneda. They were Manshi Kiyozawa (1863-1903), Haya Akegarasu (1877-1954) and Ryojin Soga (1876-1970) and their students such as Shuichi Maida (1906-1967) and Rijin Yasuda (1900-1982) – the Japanese teachers whose teachings Dr. Haneda has read, listened to and continues to study and translate.

Dr. Haneda also spoke highly of Nishi Honganji teacher Takamaro Shigaraki (1926-2014), who told American-born ministers during a visit to the United States toward the end of his life to abandon dead Honganji doctrine and convey only Shinran’s true teachings in the West.

Within the thick packet of material given to us at the retreat, this quote of Akegarasu well illustrates the divergence between “Hybrid Shinshu” and the true essence of Shinran’s teachings.

The compassion that I used to appreciate was compassion in which the Buddha carries a blind man on a vehicle while keeping the blind man blind. The compassion that I appreciate now is compassion in which the Buddha enables the blind man to open his eyes … Buddhas are compassionate not because they kindly nurture and protect me, but because with the bright light of their wisdom, they help me to open up my eyes of wisdom. [from Complete Works of Haya Akegarasu, I-2, pp. 70-75]

These points and many others made by Dr. Haneda are worthy of further study in order to grasp the true intent of Shinran’s teachings.

Rev. Nakai is minister at Buddhist Temple of Chicago, in Illinois.