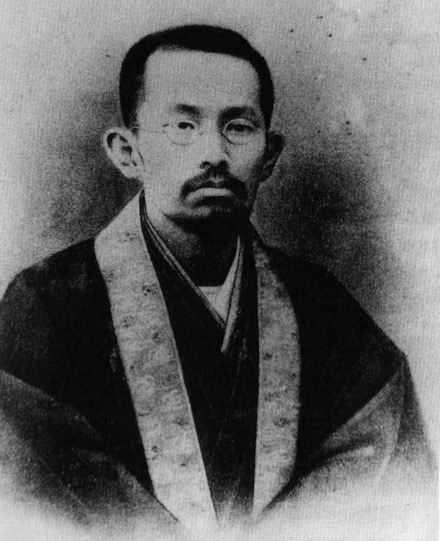

What does Jodo Shinshu Buddhism say we should do about today’s social problems, world conflict, economic uncertainty, and political instability? According to modern Buddhist thinker Kiyozawa Manshi, first think of “spirituality.”

Worldly concerns must be separated from spirituality, otherwise, each obscures the other. For those following the Buddhist path, spirituality must be first priority.

Many Buddhists would strongly disagree. Engaging in society by helping others, feeding the hungry, fighting injustice, protesting war and advocating peace not only can be part of the Buddhist path, they’re moral imperatives and ethical obligations. Moreover, doing nothing justifies criticism that Buddhism encourages passivity and limited focus on oneself.

Such discussion is highly controversial, stirring heated debate, which happened recently when I raised the subject among a group of Jodo Shinshu ministers.

Kiyozawa’s radical view raises important issues about morality and ethics which shatter widely-held assumptions about the role Buddhism should play in society, while severely questioning personal motivation and judgement. His views warrant serious consideration and further study, especially in these times of social and political unrest.

Mark Blum, Buddhist studies professor at University of California, Berkeley, explored Kiyozawa’s thinking in an essay, “Kiyozawa Manshi and the Meaning of Buddhist Ethics,” (The Eastern Buddhist, Vol. 21, No. 1, Spring 1988). Blum wrote, Kiyozawa “seems to be trying to tell us that all spiritual attainment, laying aside the question of perfectibility, must pass through, if not be based upon, a realization that all judgements of human behavior spring from a consciousness that is egocentric and severely impaired by ignorance, misconceptions, misperceptions, prejudices, etc. this is what he means by jiriki [self-power] ethics.”

Underscoring the point, Blum cites Akegarasu Haya (1877-1954), a top Kiyozawa disciple: “Akegarasu clarified this point, by saying morality and ethics can create a significant obstacle to spiritual progress by fostering an attitude of smugness and complacency in those who feel they are obeying the rules and therefore profess ‘to have no guilt about their actions.’”

The history of Buddhism through the ages, especially in Asia, is filled with priests, teachers, followers, and entire Buddhist denominations who blatantly mixed religion with politics and social action to ill effect. Sutras were chanted to protect the state, emperors declared themselves bodhisattvas, and Buddhist organizations blindly backed government policies, including declarations of war and colonialism.

During Kiyozawa’s lifetime (1863-1903), such concerns were pressing and urgent. Japan faced great social and political upheaval as the country transformed into a modern economy from a feudal state. The Meiji government (1868-1912) promoted authoritarianism, nationalism, patriotism and capitalism. Buddhism was criticized for being backward and out-of-step with modern values that emphasized pursuit of pleasure and materialism. Shinto shrines were seen as better suited for promoting the government’s agenda; consequently Buddhist organizations lost influence. In response, Buddhist leaders voiced support for government policies and mandates.

By contrast, Kiyozawa saw how religion had intrinsic value which should not be judged by worldly standards and benefits. Putting one’s spirituality at the forefront he called seishinshugi.

In a speech given in 1901, he said:

When reaching an understanding that religion occupies a different kind of locale outside any benefit to society or ethical action, one has then taken a step within it and no longer sees any need to evaluate religion from outside of it. This is the proper standpoint of seishinshugi. Therefore, rejecting external standards, seishinshugi bases its standards internally; without affixing our gaze on objective structures, we hold the subjective mental states to be essential.

Furthermore, spiritual understanding means connecting to that which is timeless, unchanging, eternal, and mysterious. Worldly benefits such as comfort, wealth, status and power occupy a completely different realm, unrelated to spirituality.

He wrote:

If we can agree that life, property, power and fame are worldly dharmas (i.e. elements, issues), then it is clear that for anyone seeking freedom, disdain for the world is essential.

Kiyozawa drew inspiration from Epictetus, a Greek Stoic philosopher and ex-slave, who’s harsh former life resulted in his physical disability. Epictetus found inner fulfillment not tied to physical surroundings or secular power. Blum cites a Stoic saying: “Athens is beautiful. Yes, but happiness is far more beautiful—freedom from passion and disturbance, the sense that your affairs depend on no one.” (from Bertrand Russell: A History of Western Philosophy)

Acting on his beliefs, Kiyozawa rallied against government accreditation for Shinshu University, where he served as president. Most students wanted their education validated by accreditation, but Kiyozawa saw secular encroachment. He feared the school turning into another of the “worldly universities set up for those seeking bread and fame.” He said: “This is out of the question. Our students are here only to deal with purely religious questions.” Students protested and Kiyozawa resigned.

Going far beyond separation of church and state, Kiyozawa’s views pierce the very nature of thought and reasoning. Buddhist teachings are based on understanding truth that is unseen, immutable, infinite and universal, which he called “superrational.” By contrast, the modern world is based on thinking that is objective and “rational.” The two realms clash by their very nature, which is why he felt rational thought must be set aside in order to grasp the superrational.

This condition wasn’t always the case, according to Kiyozawa. In ancient times, society and belief fused together superrational or religious thinking with rational or everyday thinking. In that sense, ancient people may be considered naturally religious or spiritual. However in modern times, rational thinking predominates, threatening the influence of superrational understanding to the point where it may someday be considered unnecessary.

Kiyozawa wrote:

We then must ask why present-day ethics were once ancient religion. The answer to this would have to be based on human intelligence. For today, human intelligence has developed such that we have rational ethics, but in ancient times we had superrational religion because of a lack of such development. We have two questions that must be raised at this point: 1) If we take what may be rational today and determine that it was something super-rational in the past, then can we not assume that what is superrational today may one day very well become something rational? 2) Does not this imply, then, that what was valued for its efficacy as superrational in the past has lost that value today?

Thus we have come to the point where for some people what is rational today is sufficient by itself, and there is no need whatsoever for anything superrational. And the amount [or degree] of which something is either rational or superrational is, from all points of view, still something acceptable or rationalized. We may reach a point where there is no need for the superrational, and yet we don’t know how to judge the degree of this. Probably in the end, we will never be able to establish such judgements… [hence] like in ancient times the superrational is a necessity for us today…. Thus we have no choice but to establish both religion and ethics. And from all points of view they cannot be undifferentiated.

Kiyozawa doesn’t outright dismiss the need for morals and ethics; rather, he acknowledges their efficacy and necessity in society. However, religion is a matter separate from ethical and moralistic concerns, so each side must be considered separately.

He wrote:

[Universal or religious truth] is not a teaching of morality but a teaching of religion; it is not a teaching about the path of men but about the path of Buddhas. Seeing this, it goes without saying that [universal truth] is something to be explained by a religious person, and that its goal must be to produce religious results. On the other hand, morality is morality, not religion; it is a teaching of the way of men, not the way of Buddhas. Hence, it is something that should be expounded by a moralist, and its goal must be to produce moral results. Although politicians do not avoid speaking about business matters, politicians are not merchants.

According to Blum, “Kiyozawa’s rhetoric betrays his deep concern for the necessity of maintaining religious values as such, fearing that any amalgamation of religion and ethics weakens the significance of each.” The reverse also is dangerous—religion as authority may corrupt ethics and morals.

For example, mixing religion with ethics and morality create commandments deemed necessary for salvation. Kiyozawa wrote:

In other words, because the arbitrary thought-construction, “you must do this, you must not do that,” is added to the arbitrary abstractions of ordinary morality where one is merely ordered to ‘do this, don’t do that,’ one thinks of the situation as one in which a solemn command has come down from God or Buddha saying, “you absolutely must do this,” or “it is forbidden for you to do that.” Accordingly, people come to think that the crucial matter of their salvation will depend upon their ability or lack of it to execute moral behavior…. Hence, it is natural that an extreme anxiety develops regarding one’s ability to behave appropriately.

Consequently, given our human frailties, selfishness, weaknesses, ignorance and passions, upholding high moralistic and ethical standards becomes an impossible task. Kiyozawa wrote, “Knowing we must practice ethics, why are we unable to perfect this?” He answers: “It must be because of the profound existence of the so-called habits and inherent tendencies in each one of us.”

Kiyozawa concludes ethics and morality cannot be the judge of religious salvation. Blum explained: “Liberation has nothing to do with good and evil; the real issue is ignorance and all are equally ignorant in spirituality.” Likewise, the Buddha’s monastic sangha forsook filial piety, patriotism, and social mores in committing to the spiritual path.

“Herein Kiyozawa confronted the central issue of avidyā, a sort of primal ignorance, in early Buddhism, and the doctrine that all suffering stems from conceptual delusion rooted in this deep-seated ignorance about oneself and the world that lies at the base of all we think and do,” Blum wrote.

“Instead of extolling the merits of living by moral standards, Kiyozawa instead focuses on the spiritual significance of the existential dilemma arising when we face the fact that ultimately, we can never really execute ‘appropriate moral behavior…,’” Blum wrote. “In other words, our mental afflictions, the core cause of human suffering in Buddhism, are no less relevant to the anguish we feel about our inability to lead morally perfect lives than they are to our struggle for spiritual liberation.”

According to Kiyozawa:

The intent of the worldly truth teaching of Shinshu does not lie in seeking success in the area of its execution… [it] does not aim at the usual goal of competency in the execution [of the teaching] such that we perform a credible or splendid deed…. In that case, just where does the objective of Shinshu’s worldly truth lie? Its aim, in fact, is to lead one to the perception that one cannot perform these moral tasks…. For the most basic impediment blocking the entrance of tariki faith is the thought that one is able to practice jiriki [self-power] discipline. Although there are many kinds of jiriki-disciplined practice, the most common are own acts of ethics and morality. While thinking one’s moral behavior can be carried out commendably, it is ultimately impossible to enter into tariki religion.

In short, we ultimately are incapable of living by high ethical and moral standards and that deep religious awareness lies in understanding that truth.

Nevertheless and almost paradoxically, Kiyozawa still felt ethics and morality in society are necessary, which religiously awakened people come to understand and accept.

He wrote:

The person who has attained a religious perspective inevitably realizes how imperative it is to uphold ethics… So saying this, we can state that those who do not perceive the importance of ethics have not yet entered into a religious perspective.

Kiyozawa didn’t believe in fleeing the world by joining a monastic order, which would be merely trading one set of ethics for another. Rather, the spirituality he sought was internal, in his mental processes, how he thought and felt, all while living in this world. In describing this path, he used the term, “externally a layman, internally a monastic,” which reflects Shinran’s idea of being “neither priest, nor lay person.”

Putting spirituality first while setting aside worldly concerns seems to reject social engagement. Yet, Kiyozawa devoted his life to a kind of social action by making Jodo Shinshu more meaningful to people by trying to reform the Buddhist tradition and denomination he was part of. Although those efforts failed, he became a major influence on his students, and on the Higashi Honganji denomination, which initially rejected his ideas. Today he is held in high regard and his teachings are considered a major breakthrough for understanding Jodo Shinshu in modern times.

How could Kiyozawa devote himself to such activities while dismissing worldly concerns? It seems he felt from understanding oneself springs forth action. A journal entry he made in 1898 on October 26th provides a hint:

-Daily I encounter things that I cannot control

-If I wish for things to follow my will, I must understand my limits

-It is for this reason that the desire to examine the self arises

-The result of self-examination is the desire to do good

-The desire to do good leads to Other Power faith

-Other Power faith develops into gratitude

-Gratitude (recitation of the Name in praise) becomes the desire to attain faith and teach others to have faith

-The desire to attain faith and teach others to have faith leads to the desire to practice and teach others

-And the desire to practice and teach others comes back once again to the desire to do good and so on

These are linked together as a circle

Blum wrote: “However enigmatic we may regard Kiyozawa Manshi, for someone living at a time when powerful elements of society were remarkably successful in spreading a uniform social ethic, his struggle to retrieve spirituality from what he considered the transient thoroughfare of ethical norms may truly be called heroic.”

-Rev. Ken Yamada, editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America