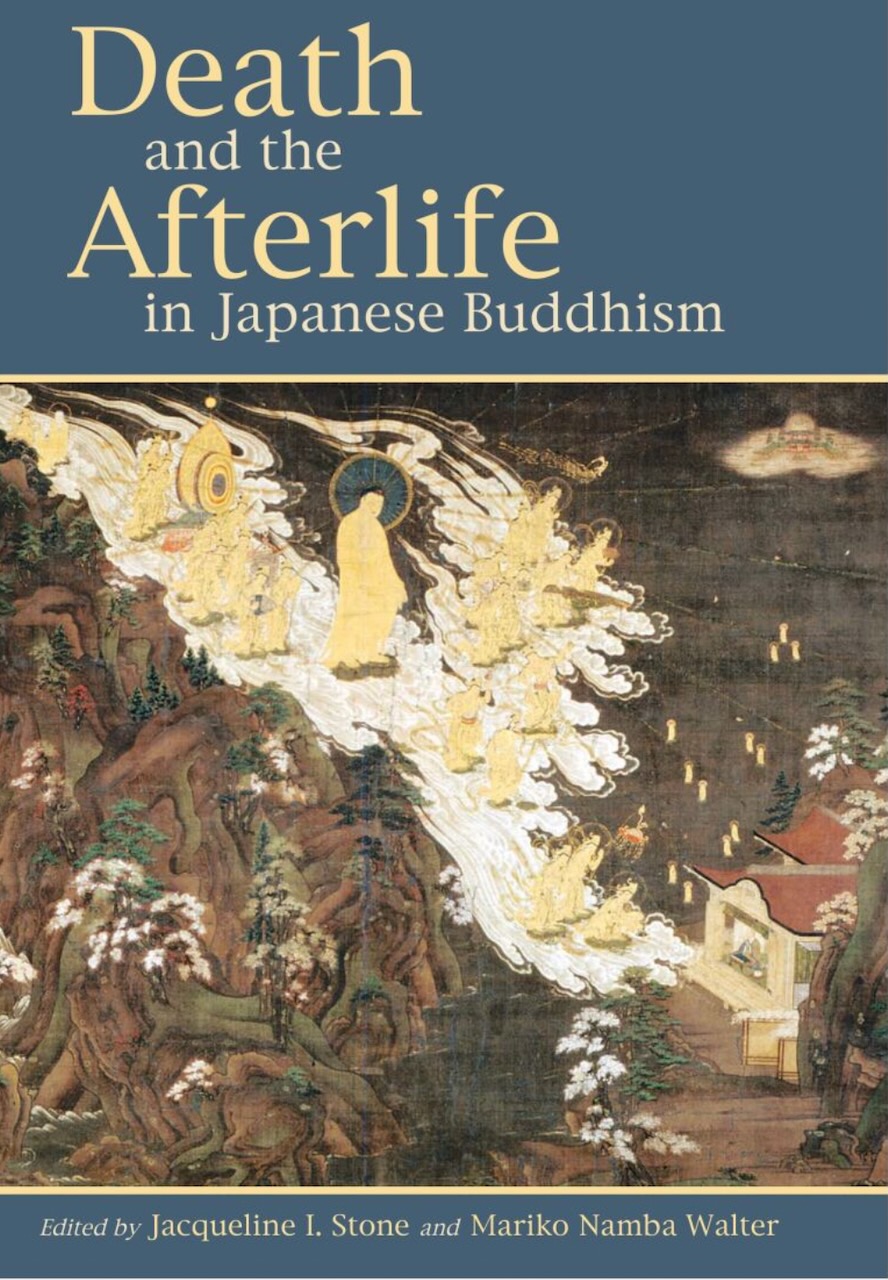

Welcoming Descent of Amida Buddha (1668) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Welcoming Descent of Amida Buddha (1668) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Japanese Buddhist rituals related to death, even today, are misconstrued and muddled in the minds of many and practiced for misunderstood reasons. Looking back at their history can clarify the confusion.

Early Pure Land Buddhist practices may be most responsible. A thousand years ago, deathbed rituals were systematized, explained and taught with the belief they would help the dying enter the Pure Land upon death. These rituals included visualizing Amida Buddha descending to guide the dying, holding a rope tied to a Buddha statue (so as not to get lost), and above all, calling the Buddha’s name by reciting nenbutsu, “Namu Amida Butsu.”

Shinran Shonin (1173-1262), the founder of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, outright rejected such practices. Instead he emphasized realization of faith, shinjin, in one’s life, and living with understanding and appreciation, rather than pinning one’s hope on postmortem bliss in an afterlife. He wrote in a letter, “there is no need for deathbed rituals to prepare one for Amida’s coming.”

As a Buddhist minister, I’ve visited many dying people in hospitals and homes. For some, I’d gently talk to the person, for others, I’d quietly chant, because it seemed calming to both patient and family. I’d always end by reciting, “Namu Amida Butsu.” After a person passes away, I’d perform a makurakyo (pillow service), consisting of chanting, a short dharma talk, and nenbutsu.

Sometimes I sensed people thought these rituals helped the deceased “go to the Pure Land,” as if the rituals were the cause, and not doing them was an impediment. However in Jodo Shinshu, these rituals, including funerals and memorial services, are performed to mark the passing of a loved one, to honor the person, to deepen our understanding of life and death, and foremost, to understand dharma—the true nature of our lives.

Prior to Shinran and Jodo Shinshu, the reasons for conducting such rituals were much different. Such practices are described in the book, Death and the Afterlife in Japanese Buddhism, edited by Jacqueline I. Stone and Mariko Namba Walter (University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), particularly in the chapter, “With the Help of ‘Good Friends,’ Deathbed Ritual Practices in Early Medieval Japan,” written by Stone, Princeton University religious studies professor emeritus.

According to Stone, Buddhist teacher Genshin (942-1017) first compiled Buddhist deathbed practices in his masterwork, Ōjō yōshū (Essentials of Pure Land birth). Shinran identified Genshin as one of the seven masters of Pure Land.

“Genshin’s recommendations for deathbed practice marked the entry into Japanese Buddhist discourse of a concern with dying in a state of right-mindfulness and belief in the power of one’s last thoughts, ritually focused, to determine one’s postmortem fate,” Stone wrote. By following certain deathbed rituals, “a lifetime of wrongdoing could potentially be reversed and even sinful men and women could achieve liberation.”

Stone wrote:

However, birth in the Pure Land was by no means a certain thing, and the discourse surrounding deathbed practices had its dark side, for the last moment was seen as pregnant, not only with immense salvific potential, but also with grave danger. If even a sinful individual who properly focused his mind on the Buddha at death might thereby reach the Pure Land, by the same token, it was thought that even a virtuous person, by a single distracted thought at the last moment, could negate the merit of a lifetime’s devotion and fall into the evil realms. To die while unconscious, delirious, or wracked by pain thus came to be greatly feared, and the importance of ritual control over one’s last moments was increasingly emphasized.

Genshin drew upon Chinese traditions to help formulate his recommendations. For example, he advised the dying person be moved to a separate room cleared of distractions, and that relatives and other visitors who recently consumed meat, alcohol or the five pungent roots (garlic, onions, green onions, chives and leeks) be kept away, lest the dying lose concentration and fall prey to demons. Those present should burn incense, scatter flowers and promptly remove any vomit or excrement. Citing another Pure Land master Shandao, he also recommended the dying face the west and visualize Amida Buddha escorting them to the Pure Land.

Referring to the 18th vow in the Larger Sutra of Immeasurable Life, which states that adherents call Amida’s name ten times, Genshin wrote about the difficulty of accomplishing such a task and suggested a work around.

Genshin wrote:

To have ten uninterrupted reflections in succession would not seem difficult. But most unenlightened individuals have a mind as untamed as a wild horse, a consciousness as restless as a monkey. Once the winds of dissolution arise [at the moment of death], a hundred pains will gather in the body. If you have not trained prior to this time, how can you assume that you will be able to contemplate the Buddha on that occasion? Each person should thus make a pact in advance with three to five people of like conviction. Whenever the time of death approaches [for any of them], they should offer each other encouragement. They should chant the name of Amida for the dying person, desire that person’s birth in the Pure Land, and continue chanting to induce [in him] the ten moments of reflection.

Genshin made other suggestions, including visualizing Amida’s physical marks, Amida’s radiant light, and descent of a holy retinue to escort practitioners to the Pure Land. For Genshin, “under the liminal influence of approaching death, the chanted nenbutsu becomes vastly more powerful than it is at ordinary times,” Stone wrote.

Accounts of Buddhist deathbed practices appeared prior to Genshin’s time, but his text was the first to systemized and comprehensively explain them, becoming an important source for practitioners during the Heian Period (794-1185) and later.

Obviously, the sick and dying may lack the strength, concentration and will to follow prescribe practices, thus arose the role of a zenchishiki (Skt. kalyānamitra, “good friend”) to assist, guide, and in some cases, serve as surrogate.

The monk Tanshū (1066-1120?) wrote in his text, Rinjū gyōgi chūki:

When one falls ill and approaches death, everything escapes one’s control… the winds of dissolution move through one like sharp swords, wracking one’s body and mind… The eyes no longer discern color and shape, the ears do not hear sound; one cannot move hands or feet or exercise the organs of sense. Even someone who is expecting this will find it hard to maintain right-mindfulness; all the more so, those of feeble attainments!… Good or evil recompense [in the life to come] depends on one’s single thought at the last moment… Those who lose the advantage of this moment are very close to hell.

Among the duties of a zenchishiki is to chant nenbutsu while matching breaths with the dying, giving the dying an appearance of chanting despite being weak or unconscious. Other tasks include nursing, such as moistening the dying person’s mouth. Another dictate said to continue chanting for hours even after death, in an effort to transfer merit to the deceased.

On this last point, I’m reminded of a memorial service I conducted a few years ago for a family whose father was a devout Chinese Buddhist. The family assured me my Jodo Shinshu rituals, whatever they were, would be fine, because immediately after passing away, members of the father’s sangha already chanted for him, taking turns chanting continuously for many hours extending over a couple of days.

Even in modern times, some groups still employ zenchishiki for rituals related to death, perhaps most notably people following secret forms of Jodo Shinshu.

Stone wrote:

The thrust of medieval deathbed ritual instructions was increasingly to construct the zenchishiki as a sort of deathbed specialist. With him rested the ritual control of the final moment, with its brief window onto the possibility of escape from samsaric suffering… Over time, it is he, even more than the dying person, who comes to be represented as ultimately responsible for that person’s success or failure in reaching the Pure Land.

Aspiring for birth in the Pure Land, or some other heavenly realm, was a generic goal that cut across other Buddhist traditions and was not limited to Pure Land, according to Stone. For example, Hossō (Skt: Yogācāra) practitioners recommended swapping Amida’s image with Maitreya’s image in order to aspire for birth in Tusita heaven. Nichiren Buddhists recommended chanting “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō,” the Lotus Sutra’s name. Shingon Buddhists recommended the image of deity Fudō Myōō, depicted with sword and scary face, as a protector against demons at the moment of death, or focusing on the image of Shingon’s founder Kūkai (774-835). According to Stone, detailed instructions in Shingon even included a five-colored cord tied to a Buddha statue, “their threads should be spun in a purified room by a woman approaching eighty (and thus, presumably, free from sexual impurity), dyed the five colors by a holy man (hijiri)… ”

These practices were not limited to monasteries. Members of the emperor’s family, the court and aristocrats observed such practices, documented in biographies and official accounts, representing an ideal death. Stone pointed out conflicting accounts portrayed more realistic and unseemly deaths filled with pain, delirium and loss of bowel control. Deathbed practices also were observed by some in lower classes.

In 1185, at the end of a civil war in which the Minamoto clan defeated the Taira, monk Honjō-bō Tankyō served as zenchishiki to ensure Taira leaders didn’t depart this life bearing grudges that would transform them into “dangerous vengeful ghosts.” An account is described in the classic novel, “Tale of the Heike,” in which defeated commander Taira no Shigehira holds a cord tied to the hand of a buddha image while chanting nenbutsu, as an executioner cuts off his head.

Prominent Buddhist teachers dismissed these practices as misguided, useless and contradictory to Buddhism. For example, Stone wrote that Shingon monk Kakukai (1142-1223) “suggests that, for Buddhists, who should understand the emptiness and nonduality of all things, there is something improperly self-obsessed about fixing one’s aspirations on a particular postmortem destination.” Kakukai wrote, “The circumstances of our final moments are by no means known to others, and even good friends (zenchishiki) will be of no assistance.”

While not entirely dismissing the role of a zenchishiki, Shinran’s teacher, Jōdōshu founder Hōnen, viewed reliance on them as possibly subverting a devotee’s trust in Amida Buddha, undermining nenbutsu recited in daily life.

In a letter to retired emperor Go-Shirakawa’s daughter, Hōnen declined to act as zenchishiki at her deathbed, saying, “You should abandon the thought of an ordinary person (bonbu) as your good friend, and instead rely on the Buddha as your zenchishiki… Who would [be so foolish as to] relax one’s reliance on the Buddha and turn [instead] to a worthless, ordinary zenchishiki, thinking slightingly of the nenbutsu one has chanted all along and praying only for right thoughts at the last moment? It would be a grave error!”

According to Stone, Shinran took the most radical stance against deathbed rituals. She wrote, “Shinran understood the certainty of salvation as occurring, not at the moment of death, when one would achieve birth in the Pure Land, but at the moment when, casting off all egoistic reliance on one’s own virtues and entrusting oneself wholly to Amida, one is seized by the Buddha’s compassion, never to be let go, and faith arises in one’s heart. This led him to reject the need for deathbed practices altogether.”

In a letter, Shinran wrote:

When faith is established, one’s attainment of the Pure Land is also established; there is no need for deathbed rituals to prepare one for Amida’s coming,” Shinran wrote. He also wrote, “Those whose faith is not yet established are the ones who await Amida’s coming at the time of death.

In another letter, Shinran wrote:

The person living the true life of the mind of faith has already been welcomed in by the Buddha and dwells in the ranks of those truly determined for birth. For that reason there is no need for them to pray for the Buddha to welcome them on their deathbed. When your heart is reoriented to the mind of faith, at that very moment your ascent to birth is also determined.

For Shinran, attaining a mind of shinjin in this life, was utmost important. Any postmortem afterlife seemed beside the point. In the text, Tannisho, he said:

I have no idea whether the nenbutsu is truly the seed for my being born in the Pure Land or whether it is the karmic act for which I must fall into hell. Should I have been deceived by Master Hōnen and, saying the nenbutsu, were to fall into hell, even then I would have no regrets.

In Jodo Shinshu, all rituals and ceremonies are ways for us to understand dharma, great truth, and to encourage us to appreciate this life and our connection to everything and everyone around us. This is Shinran’s message, not only today, but during a time when people thought and practiced rituals with a very different meaning.

-Rev. Ken Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America