By Bishop Kenjun Kawawata

These days, my body has become “koki koki” (stiff and jittery), especially this year at 70 years old, called “koki” (古希) in Japan. Long ago, this age was considered “old” and “rare.” Yet in my head, I’m not an “old man.” I wonder, does long-life mean happiness?

Considering my age, indeed I’m old. My face shows wrinkles and spots, my hair has disappeared, and my memory is rusty. I miss important parts of conversation, especially with my wife, seemingly hearing what’s convenient and deaf to what’s disagreeable.

Everything about me droops and falls—eyelids, cheeks, chest and tummy. Gravity pulls downwards, making me smaller. Eventually, I’ll become Earth’s soil. Once born in this world, we grow older and die. Before, life spans typically were 50 years; now, people can live 100 years or more.

What’s the meaning of living 100 years? Do people live long by their own efforts? Jodo Shinshu says the opposite, that we are allowed to live—“Life is living you.”

This truth makes our lives strange and wonderful.

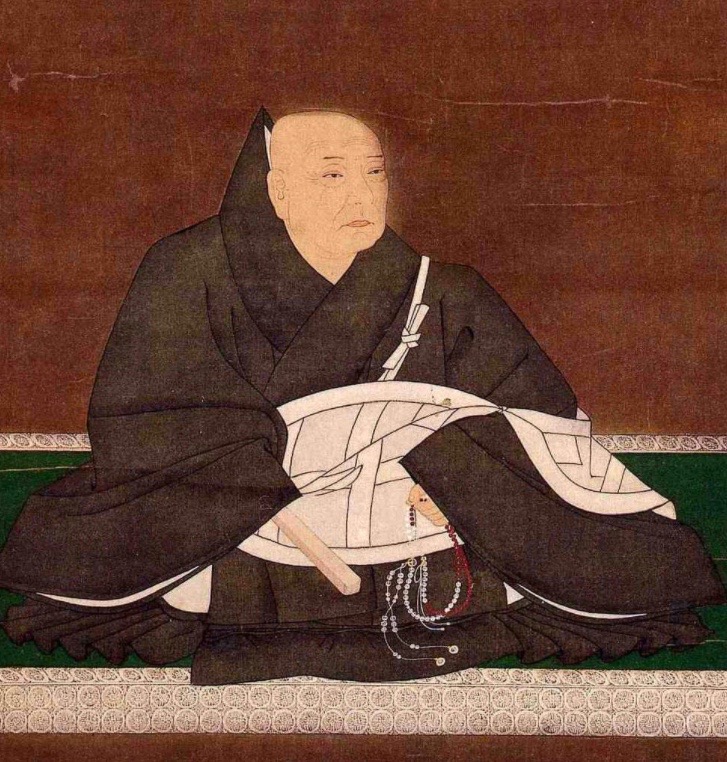

The “second founder” of Jodo Shinshu, Rennyo Shōnin, wrote:

As fall and spring slip away, the months and years go by; yesterday is spent, and today draws to a close. Little did I know that I would grow old before I was aware of it, with the unnoticed passage of the years. Yet, on occasion during that time, I must have known the beauty of flowers and birds, the wind, and the moon; I must also have met with the joy and sorrow of pleasure and pain. But now there is not even a single instance that I remember in particular. How sad it is to have grown gray with age, having done no more than pass nights and days to no purpose. But when I deeply reflect on the apparent soundness of my own existence, not yet having been called away by the relentless wind of impermanence, it seems like a dream, like an illusion. As for now, there is nothing left but to aspire to the one way of getting out of birth-and-death. And so, when I hear that it is Amida Tathāgata’s Primal Vow that readily saves sentient beings like ourselves in this evil future age, I feel truly confident and thankful.

(Rennyo Shonin’s Letters, IV-4)

During these pandemic times, life is particularly fragile and precarious. We fear Covid-19 and mutating variants, especially if we’re older or have weakened health. No one wants to get sick or die.

The Buddha tells us: All are born from “dependent causation” (innumerable causes and conditions), we live because of “dependent causation,” and we die because of “dependent causation.”

Birth means a life of growing older, suffering illnesses and dying. It’s true for everyone. Deep within us, there’s a “wish”—aspiration for life—coming from a place beyond the ego. It’s the desire to live life to the fullest and to die with satisfaction. We each have our own way of fulfilling our life and we’re all searching for it.

In his letter, “On an Epidemic,” Rennyo wrote,

Recently, it is said that many people are dying from the plague and illness. However, we do not die mainly from infectious diseases. It is because of our karma, which is determined from the moment of our birth. We should not be so deeply surprised by this. And yet, when people die at this time of life, everyone wonders. It is really quite rational.

According to Rennyo, the moment of birth determines human death, so we shouldn’t be surprised when people die. This is the fundamental problem. However, we humans point to various causes of death, depending on the person. It may be from disease, a car accident, war, old age, whatever. The reasons vary. These days, we often hear the cause is Covid-19.

But one thing is certain and always true—the ultimate cause of death is birth. If there is birth, death follows. Without birth, there’s no death. This is ultimate truth. This is Dharma.

The Buddha points to four kinds of great suffering: birth, sickness, aging, and death. Human life means inevitably experiencing these kinds of suffering. Just because death is certain, doesn’t mean we should feel desperate, nor does it mean chasing selfish desires.

Then, how should we live? That’s our challenge. First, understand we have received this life. It’s the result of countless karmic causes and conditions. We are inter-connected with countless people—our family, friends, community, and so on, as well as to the world around us—plants, animals, forests, rivers, fields, rivers, oceans, and more. In other words, we are connected to the entire universe and to each other.

When we understand this connection, we know we are part of a greater whole. We realize how our actions affect others, and understand our responsibility to each another.

When the Buddha attained awakening, he realized, “I am impermanent, my body and mind are always changing and moving.” He understood the changing nature of existence and that death too was part of his life.

In daily life, we tend to ignore or forget the true nature of human existence. We put a lid on inconvenient truths and unpleasant thoughts. In our minds, we close our eyes and can’t see Truth. In Buddhism this darkness is called “ignorance.”

The Buddha’s teachings provide the light of wisdom that helps us break through the darkness. Let’s listen to the Buddha dharma, rely on this light, and face this pandemic together.

-Bishop Kawawata oversees the Higashi Honganji Hawaii District and is based in Honolulu.