By Rev. Ken Yamada

Who’d think Shinran Shonin, founder of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, could stir controversy 750 years after he lived? With much speculation, today’s scholars are exploring new angles of his life, which may prove a different Shinran than the one we know.

For example, did you know Shinran was married more than once? This “other” woman was considered his true wife up until modern times. Personally, I had no idea. See below for more.

Scholars of Shin Buddhism and Japanese history continue to research available materials hoping to clarify and discover previously unknown facets of Shinran (1173-1263). Professor Michael Conway of Otani University discussed new perspectives on Shinran’s life in a presentation to Higashi Honganji ministers last March in Los Angeles.

Professor Michael Conway

While findings up to now are subject to much debate, they open the door to furthering our understanding of Shinran’s life and experiences, filling in blank spots and possibly shedding light on his thinking, motivations and actions beyond standard narratives given by textbooks and institutions.

Typical biographies cover basic highlights: A parent-less Shinran is ordained as a child, spends 20 years in a monastery, leaves, becomes a disciple of Hōnen, is exiled to the countryside, marries, has children, meets with villagers and eventually lives out his life in Kyoto. Many details are missing and unknown, leaving today’s scholars scrambling to fill in the blanks.

For example, researchers pieced together a family tree showing how his ancestors—members of the Hino family (a branch of the illustrious Fujiwara clan)—held high positions in the Emperor’s court. The family was known for its Confucian scholars. According to one family tree, several of them held the title “doctor of letters,” which enabled them to serve in government, although not necessarily in high positions. Governing, including rule making, etiquette and correspondence, were based on Confucian principles similar to government in China, so knowledgeable scholars were needed as advisors. Among the bunch, Shinran presumably had a dissolute grandfather with perhaps a drinking problem.

In keeping with the family legacy, Shinran’s father, Hino Arinori, presumably held a middle rank administrative position. The standard narrative says he somehow lost his position, forcing him to give up his family—Shinran among them. Some textbooks speculate the father’s death was the reason why Shinran became a monk on Mt. Hiei.

However, Zonkaku (a fourth-generation descendent of Shinran) owned a copy of the Larger Sutra of the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life, with an inscription saying it was made by Shinran, his brother, and his father, when they all were adults. This claim raises the possibility that Shinran’s father had not died, but rather, entered the priesthood. Thus, another question arises: Did Shinran’s father commit an egregious error forcing him from the court, or was there another reason he entered the priesthood?

Whatever the case, Arinori lost his position during a time of great social upheaval. Two major clans, the Taira and Minamoto, were fighting the Genpei war, each vying for power. The Hino family was connected to the Minamoto clan, so political turmoil may have affected Arinori’s position, although the Minamoto clan eventually won the war and seized power. Another possibility: Shinran’s mother, Kikkōnyo, may have been related to the Minamoto clan. Nothing more is known about her.

Hokkaiji temple in Kyoto was devoted to the Hino family, and according to a sign there, it was Shinran’s birthplace, although scholars remain skeptical. Another question arises: Did Shinran enter the priesthood to eventually become caretaker of Hokkaiji?

At age 9, Shinran was taken to Shōren-in temple in Kyoto to become a monk. He was received by head priest Jien (1155-1225), who’s depicted in art with a big, floppy nose. Jien was the brother of Kujō Kanezane, who served as imperial regent of Japan (1186-1196), and who later became a disciple of Shinran’s teacher Hōnen. Jien became a distinguished and high-ranking monk, eventually heading Tendai Buddhism.

Jien

A biography written by Kakunyo (Shinran’s great grandson) explains Shinran’s ordination as follows: “Although he was a person who should have grown old serving the court, receiving laurels for working in the palace, because of a desire to spread the Dharma budded within him, conditions without came together to allow him to benefit living beings…”

However, some scholars question if a desire to learn Buddhism really motivated a 9-year-old boy to enter the priesthood, or if there was another reason, for example, related to pressures from family, politics or society. In any event, Shinran likely was ordained with his three brothers, all younger. His brothers are usually not mentioned in Shinran’s biography.

Ordination

Shinran became a monk on Mt. Hiei, home to Tendai Buddhism, which was founded by Saichō (767-822). In order to establish Tendai, Saichō stated his case for establishing a new religious order to the imperial court, explaining:

What is the treasure of the nation? The treasure is the mind that seeks enlightenment. We can call a person with the mind that seeks enlightenment the treasure of the nation. Therefore, a person of old has said, “Ten inch-round jewels are not the treasure of the nation. One who shines in one corner is the treasure of the nation.” A wise one of old also said, “One who can preach but cannot practice is a teacher of the nation. One who can practice but not preach is the servant of the nation. One who can both preach and practice is the treasure of the nation. Among these three, just one who can neither preach nor practice is the bandit of the nation.”

Saichō traveled to China, where he learned from Chih-i, who taught austere practices that included 90 days of sitting meditation in a chair without moving or laying down, and constant walking meditation while chanting Amida Buddha’s name. Less severe forms included meditating or chanting for seven or three days. Shinran served as dōsō, hall attendant, on Mt. Hiei and probably practiced shorter length meditations for the benefit of deceased members of aristocratic families, who paid honorariums to the priests.

In looking at why Shinran gave up his monastic life, Dr. Conway explained how practices on Mt. Hiei were based on Sachiō’s emphasis on the Single Vehicle teaching, taught in the Lotus Sutra. A story in the sutra known as the Three Carts, describes children playing in a house, unaware it has caught fire and is burning. Their father pleads with them to escape, but they refuse. He promises gifts of three carts, pulled by a goat, deer and ox. The children escape but find only one giant cart pulled by a large white ox.

Symbolically, the deer cart represents solitary practices such as those done alone in the forest; the goat cart represents a docile animal following a herder, much like a disciple follows a master; and the ox cart represents working hard towards a goal. The giant cart represents a single vehicle, which everyone may board, symbolizing an egalitarian Mahayana Buddhist path open to everyone. However, Mt. Hiei practices were extremely severe and required great discipline and perseverance, qualities limited to a chosen few and requirements that must have frustrated Shinran.

Legends in Japan abound about Shinran’s life, such as a story I heard about a tree that grew where Shinran left his walking stick. Once when I visited Shōren-in, a priest explained that a lock of Shinran’s hair was kept behind the altar, which I didn’t really believe because Shinran was a relative unknown when he received tonsure so why would the temple keep his hair?

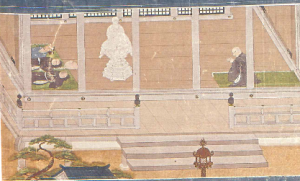

And then there’s a story of how a young monk Shinran turned away a woman who asked to learn the dharma on Mt. Hiei, explaining women were forbidden from going to the mountain.

According to Takada-ha, a small Jodo Shinshu denomination, Shinran stopped at Sekisan shrine in Kyoto, where he encountered the woman asking to be taken to Mt. Hiei. She challenged him, saying, “Doesn’t Buddhism preach that everyone can be liberated, regardless of age or sex or wealth or status?” Scholars think this story originated in the 14th Century, after Shinran’s lifetime.

However, that event, or at least that kind of awareness of how practices on Mt. Hiei were exclusionary and difficult, may have contributed to Shinran’s frustrations and decision to leave. The austere and elitist path he followed for 20 years surely didn’t represent the Great Vehicle teachings meant for all people. Shinran was unable to follow such practices and unable to preach them, making him a “bandit of the nation,” at least according to Sachō’s edict. We can only guess the reasons.

Rokkakudō

Ultimately, Shinran left Mt. Hiei at age 29, traveling to Kyoto, where he began a 100-day seclusion before a statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Japanese: Kannon Bosatsu), the central figure at Rokkakudō temple. According to Kakunyo’s biography, on the 95th day Shinran dreamed of Avalokiteśvara:

Kannon of Rokkakudō took the form of a monk with well-proportioned features, wearing a white robe. Sitting straight on a large white lotus, he told Zenshin (Shinran): “If any practioner, because of his past karma, commits nyobon (noncompliance with the system of Buddhist monastic precepts concerning contact with women), I will take on the bodily form of a precious stone woman, a noble life-preserving deity, gyokunyo, and accommodate the rule-breaking. I will adorn him all his life, leading him at death, I will cause him to be born in the Land of Ultimate Contentment.” Having recited the verse, the bodhisattva continued, saying, “This is my sworn vow. Preach to all living beings and let them know about the significance of this vow.”

Because Shinran was a celibate monk, it’s often assumed this dream expressed his carnal desires. However, the dream continues:

At that time, while still dreaming, looking to the right when facing the front of the temple building, he saw a towering mountain and on that mountain several hundred billion beings had gathered. Then, according to the order, he explained the significance of this passage to the sentient beings gathered on that mountain. When he felt he had finished, he awoke from the dream.

In a historical picture scroll depicting the dream, people of various classes—merchants, farmers, warriors, both men and women—are shown walking along a path towards Shinran.

In ancient Japan, people placed great importance on dreams, influencing how they thought and acted. People sometimes slept on the large porches and covered walkways of temples hoping for an auspicious or influential dream.

After Shinran had his dream, he immediately departed Rokkakudō to see Hōnen, who taught him about the Nenbutsu, sole reliance on reciting the name of Amida Buddha. If Shinran were compelled by his earthly desires, he could have visited a brothel or immediately gotten married, Dr. Conway said. Instead he visited Hōnen, seeking guidance for himself, which ultimately benefited other people. Therefore, the dream represents the idea that following precepts is unnecessary for attaining spiritual awakening and helping others.

Even so, Shinran didn’t seem quickly sold on Hōnen. According to a letter that his wife Eshinni later wrote, Shinran did not decide to commit to Hōnen for a hundred days, which can be seeing as wavering. Perhaps Shinran struggled with the idea of giving up the ages-old Buddhist tradition of the threefold path he learned on Mt. Hiei, based on precepts, meditation and wisdom, before he could commit to Hōnen’s version of the Single Vehicle teaching.

When Hōnen incurred the wrath of authorities, he and a few of his disciples were exiled to various places. Shinran was sent to Echigo province near the Japan Sea. As the story goes, he lived there with his wife and children.

Perhaps the biggest change to this narrative involves his marital status. His standard biography says Shinran married Eshinni and had six or seven children. However, Eshinni was unknown until 1921, when a small collection of her letters was discovered in the Nishi Honganji archives, which confirmed her existence and provided valuable details about Shinran’s everyday life. Until then, tradition held that Shinran’s wife actually was another woman named Tamahi. Still today, the Takada-ha denomination cites Tamahi as Shinran’s main wife.

Tamahi was thought to be a daughter of Kujo Kanezane (1149-1207), who was an imperial regent, an official who acted on behalf of a child emperor until his coming of age, which meant that Tamahi most likely had a privileged upbringing in Kyoto. Eventually, Kanezane became a follower of Hōnen. Given those circumstances, Hōnen may have encouraged Shinran to marry Tamahi in Kyoto. A pictorial scroll of Shinran’s life depicts a scene, “Three men have the same dream,” showing Kanezane, Hōnen and Shinran sleeping near a statue of Kannon, symbolizing the trio’s connection to Tamahi.

Therefore, it’s possible when Shinran was exiled to the hinterlands of Echigo province, Tamahi stayed behind, preferring her privileged life in Kyoto, or perhaps was unable or unwilling to suffer foreseen hardships.

Consequently, Tamahi could have arranged for Shinran to marry Eshinni, who was a lady-in-waiting in the Kujō household. Or perhaps Eshinni already was living in Echigo, where her father or uncle had a high-ranking position in government.

Whatever the case, Shinran and Eshinni lived together, raising a family of six or seven children far from the capital in a rural region, known for harsh winters. Shinran often is imagined as living among common folks, perhaps even tilling the land. Reality likely was much different.

Typical exiles were given a year’s worth of rice, seed, and salt, the logic being—eat the rice and salt while planting the seeds, then the following year’s crop becomes your sustenance. However, Shinran was not a typical exile.

He had a top education from Mt. Hiei and could read and write classical Chinese, during a time when most commoners were illiterate. Shinran likely put his abilities to work, perhaps by drafting documents and letters for other people. According to Japanese historian Masaharu Imai, Shinran tilling the fields is unimaginable, considering the era’s social structure.

Moreover, Eshinni may have been the daughter of Miyoshi Tamenori, who served as assistant governor of Echigo and who was appointed by Kanezane. If so, Shinran’s exile to the province was carefully planned, allowing him to be supported by his wife’s family. Eshinni’s letters refer to a home life with servants. A householder with servants unlikely would have eked out a living by doing manual labor.

Shinran’s life story probably was influenced by Victorian values governing morality promoted by religious institutions, according to Ayako Osawa, a researcher at Otani University, whereas a biography depicting a monogamous marriage and socially accepted nuclear family sends a more wholesome image.

Among the aristocracy in medieval Japan, men with multiple wives and concubines were not uncommon. Consequently, a Shinran with two concurrent wives may not have raised eyebrows, let alone a person once divorce and remarried. However that image may be troubling to temple members, even today.

We may never know the exact details of Shinran’s life. Scant evidence remains to either prove or debunk swirling speculation. In academia, that challenge won’t stop scholars from trying.

-Rev. Ken Yamada is editor of Shinshu Center of America.

Sources:

“New Perspectives on Shinran’s Biography,” lecture notes, Professor Michael Conway, Ōtani University, Los Angeles, March 3, 2020

“Constructing the Couple Image of Shinran and Esshin-ni in the Modern Period,” abstract, Ayako Osawa, Otani University (Tokyo branch), presented at the International Association of Shin Buddhist Studies meeting, Taiwan, May 25, 2020

“Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan,” by E. Papinot, Charles E. Tuttle Company, Tokyo, 1982

“Letters of the Nun Eshinni, Images of Pure Land Buddhism in Medieval Japan,” by James C. Dobbins, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 2004

“Life of Shinran Shōnin” by Kakunyo Shōnin, translated by Gesshō Sasaki and Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki, Shinshū Otaniha, Kyoto, 1973

“Shapers of Japanese Buddhism,” edited by Yusen Kashiwahara and Koyu Sonoda, Kōsei Publishing Company, Tokyo, 1994

“Shinran, An Introduction to His Thought,” by Yoshifumi Ueda and Dennis Hirota, Hongwanji International Center, 1989

“The Essential Shinran: A Buddhist Path of Entrusting,” edited by Alfred Bloom, World Wisdom Inc., 2007

Image: Shinran and Woman, Shōren-in Temple, Kyoto