By Rev. Ken Yamada

Jodo Shinshu Buddhism teaches birth in the Pure Land. But what exactly is the Pure Land?

Disagreements abound—a heaven-like place where you go after death; a higher realm of consciousness; spiritual understanding in this life.

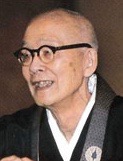

That debate reached a fevered pitch in 1920s Japan with priests, intellectuals, journalists, and laypeople weighing in. The most infamous perhaps was Shin scholar Kaneko Daiei (1881-1976), who asserted the Pure Land wasn’t a place, but rather an “idea.”

A firestorm of criticism ensued as scholars, priests, and laypeople holding more orthodox views lashed out. Buddhist sect authorities quickly hurled accusations of heresy. Blowback followed as students protested, academic staff resigned and others were fired. Threatened with excommunication, Kaneko was forced to resign his teaching post at Higashi Honganji’s Ōtani University.

Kaneko wrote: “I chant the nenbutsu and visit the Pure Land. This was the belief of our parents, which we remember fondly. However, [nowadays] educated people find it difficult to sympathize with this belief and consider it to be merely the superstition of the elderly. This is a question that I have been asking myself since I was a child.”

Shinshu teachings describe the Pure Land as follows:

The Buddha replied to Ānanda, “The Bodhisattva Dharmakāra has already attained Buddhahood and is now dwelling in a western Buddha-land, called “Peace and Bliss,” a hundred thousand kotīs of lands away from here.

(Larger Sūtra of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life)

Shariputra, in that world there are lotus ponds whose shores are decorated with seven kinds of jewels. The ponds brim with waters of eight good qualities and the floor of the ponds are lined with sand of gold. The ponds are surrounded by steps on their four sides made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and crystal. Above are pavilions lavishly adorned with the seven jewels of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, crystal, coral, red pearls, and agate.

When the thought of saying the Nembutsu erupts from deep within, having entrusted ourselves to the inconceivable power of Amida’s vow which saves us, enabling us to be born in the Pure Land, we receive at that very moment the ultimate benefit of being grasped never to be abandoned.

Following the spiritual lineage of Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), Kaneko sought to interpret Jodo Shinshu through modern philosophical thought and personal experience. At the time during early 20th Century Japan, rational and scientific thinking gained influence, pushing aside centuries old beliefs, deemed outdated or superstitious.

Murayama Yasushi analyzed the “Kaneko problem” in an essay “Heresy and Freedom of Inquiry in Interpreting the Pure Land: An Introduction to Kaneko Daiei’s ‘My Shin Buddhist Studies’” in The Eastern Buddhist journal (2021), an essay originally published in Japanese in 2012.

Murayama wrote:

The word “modernization” has many meanings. One understanding of it in the context of Japan sees it as the process of historical change through which preexisting ideas were reinterpreted in light of Western thought, which arrived piecemeal throughout the Edo period [1603-1868]. These Western-inflected interpretations gained a significant number of new supporters and subsequently became broadly influential (whether in harmony with, or in opposition to, the progress of capitalist society). If “modernization” is understood as this process of popularization, then Kaneko can be said to have supplemented Kiyozawa’s project of modernization. Nonetheless, Kaneko modernized Pure Land thought from a different perspective than that of Kiyozawa.

According to Murayama, during Japan’s feudal era, ordinary people believed birth in the Pure Land meant an actual world in the West with wonderful features that could be experienced with one’s senses.

Jeff Schroeder, in his book The Revolution of Buddhist Modernism, Jōdo Shin Thought and Politics, 1890-1962, documented Kaneko’s heresy case. He wrote how—prior to Japan’s emergence as a modern society—free inquiry was discouraged and heresy accusations were commonplace throughout Jodo Shinshu’s history.

According to Schroeder, “Ordinary temple priests were not permitted to discourse freely on the Kyōgyōshinshō but could only engage in the practice of ‘reading together’ (kaidoku 会読), a circumscribed, question-and-answer form of lecture.” Higashi Honganji, for example, sent representatives to investigate the accused, provide orthodox instruction, and if necessary, and punish offenders with home confinement, banishment to distant provinces, or expulsion from the sect.

In a changing Japan, denomination authorities could not exert such heavy-handed measures against Kaneko. Moreover, the controversy spilled into public view when a Buddhist newspaper published the charges, stirring an outcry of voices, both for and against.

According to Schroeder, the controversy erupted when Kaneko lectured on the Pure Land as an “idea” concept, apparently shocking various laypeople in attendance, including a wealthy businessman who was a member of Higashi Honganji’s accounting directors committee. The businessman later complained, sparking a defund-the-university proposal and an inquiry by denomination authorities, who concluded Kaneko’s writings had indeed contradicted the sect’s teachings.

After multiple heated meetings, an agreement was forged, allowing Kaneko to “voluntarily” resign, leaving the door open to reinstatement later. The deal avoided a messy public trial, a certain verdict of heresy and Kaneko’s likely excommunication. However, a short time later, Kaneko resigned from the priesthood, presumably because of continued pressure.

A year later in 1930, the controversy again flared when Soga Ryōjin, another prominent Shin scholar, resigned from Ōtani University in Kaneko’s support, prompting a new wave of student protests, critical press, firings and budget cuts. According to Schroeder, “all faculty and staff at Ōtani University resigned en masse, and the entire body of over eight hundred students withdrew.” A truce was reached, but university president Inaba Masamaru was forced to resign. Later, both Kaneko and Soga were reinstated and returned to the university.

What in Kaneko’s writings caused such vehement opposition?

First consider the zeitgeist of the times—after centuries of feudalism, fresh ideas from the West flowed into the country, especially the spirit of free and open inquiry that challenged assumed beliefs and spurred new ways of thinking.

In this atmosphere, Nonomura Naotarō, a professor at Nishi Honganji’s Ryukoku University wrote an essay “Critique of Pure Land Buddhism,” outright denying the existence of the Pure Land, dismissing it as a useless myth. Nonomura wrote, “The idea of birth in the Pure Land is [an outmoded way of thinking] from the past, and this idea should no longer be accepted in the present or the future.” Consequently, he was ousted from the denomination and resigned his teaching post.

By contrast, Kaneko didn’t deny Pure Land’s existence, but rather, searched for personal meaning related to his life. While he couldn’t blindly believe in a Pure Land after death, he felt it somehow represented something important.

Responding to Nonomura’s thinking, Kaneko wrote, “Yet today, even though the idea that faith and religion are entirely possible without concepts like the Pure Land has become quite prevalent, I just cannot be satisfied with that and have been possessed with the thought that in fact the Pure Land must hold some sort of significance for us.”

On this matter, Kaneko’s spiritual mentor Kiyozawa offered no answer. In emphasizing personal experience, Kiyozawa felt he couldn’t comment on Pure Land’s veracity. He had written, “I have not yet experienced the happiness of the next life. Therefore, I can say nothing about it here.”

Drawing from reasoning derived from Kant and Plato, Kaneko analyzed Pure Land from three perspectives: Pure Land as Actual Existence; Pure Land as an Ideal; and Pure Land as an Idea. He defined them as follows:

-“Pure Land of Actual Existence” means believing in a place that exists somewhere to which we go through our own efforts, as sutras describe.

-“Pure Land as an Ideal” means a place not existing now, but which can be realized or materialized later through human effort. For example, citizens may uphold an ideal of an ethical and moral society and work towards a goal of bringing it into existence. Kaneko wrote this kind of Pure Land is “nothing more than a sort of theory of morality and not something that can genuinely save us.”

-“Pure Land as an Idea” means an “absolute ideal” not attainable by human effort, no matter how hard we try. It’s existence doesn’t matter because it transcends our individual existence. It’s “a world as yet unseen, yet also the familiar home for which we long,” Kaneko wrote. It’s “the real world in the true sense of the word.” Kaneko focused most on this Pure Land.

“Pure Land as an Idea” he described as “absolute,” “pure,” and “a priori.” The term “a priori” denotes reasoning or knowledge derived from theoretical deduction, rather than empirical observation. Such words indicate a transcendent reality.

In another essay (“A Dual World”), Kaneko wrote: “Is the nirvana that we long for and seek in fact literally emptiness?… If anything, nirvana is the true existence, and our world of various beings is nothing but emptiness.” It’s “the real word in the true sense of the word.”

As Kaneko’s views became known, a torrent of harsh criticism followed. Murakami Senshō, former Ōtani University president, declared that sutras clearly state the existence of a Pure Land in the West with specific adornments, all of which cannot be refuted. He wrote that Kaneko’s error came from understanding Buddhism through Western philosophy, which was “an attempt to pander to the ideology of young people.”

For Murakami, compassion in Shinshu meant “abandoning all reason and logic and simply accepting salvation as beyond conceptual thought.” All are embraced, even those lacking in capacity to engage in lofty philosophical thought, which includes “people in the lower classes.”

Other arguments against Kaneko include: free inquiry isn’t allowed in this case because his views conflict with sect doctrine; he disregarded scriptural evidence; he confused philosophy with religion; and he shifted Shin’s emphasis away from compassion towards wisdom.

In his argument, Tada Kanae, a Kiyozawa-follower-turned-critic, pointed to three kinds of understanding.

-“Transmitted Dharma,” referring to truths revealed by Śakyamuni Buddha, Shinran, and succeeding patriarchs, according to scriptures.

-“Individual Realization,” which means understanding those Buddhist scriptures for oneself.

-“Personal Understanding,” meaning realization based on one’s experience and ideas.

According to Tada, Kaneko’s view was a form of “personal understanding,” not based on scriptures. Moreover, Kaneko’s introspection relies on human reasoning, which is tainted by dualistic and self-power thinking. Introspection is for “Path of Sages” monastics, not appropriate for foolish, ordinary people. Instead, Shin followers receive dharma by humbly listening, which is a passive, not active path.

According to Schroeder,

Kiyozawa, and Soga and Kaneko after him, held out hope for a certain level of consensus in regard to doctrinal interpretation. Kiyozawa believed that authentic experiences of unification with the Infinite would give rise to a shared understanding that Amida, the Primal Vow, hells, and pure lands all relate not to the distant past or the future awaiting us after death, but to our present experience. Kaneko and Soga believed that the “facts” of religious experience could serve as a reliable foundation for a new, systematic Shin studies to be practiced in common by all earnest seekers of Shin Buddhist truth. Kaneko’s heresy incident revealed the limits of this vision.

Over the next several decades, the study and practice of Shin Buddhism within the Higashi Honganji denomination gradually became more open in the spirit of free inquiry, aimed at better understanding and appreciating the teachings.

Nearly twenty years after facing heresy charges, Kaneko wrote:

Do paradise and hell really exist? If yes, then won’t someone [like me] who doubts their existence be the first one to end up in hell? This was the anguish of my young mind at age eight or nine. When I think back on it now, this doubt was destined to shape my life. Thanks to that early anguish, I can now feel the guidance of the teachings deeply within myself. Therefore, I intend to continue to study the true meaning of these teachings.

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji’s Shinshu Center of America