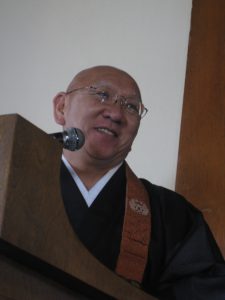

By Rev. Kenjun Kawawata

The famous Zen scholar Daisetz Suzuki spent a lifetime translating and writing about Buddhism emphasizing Dharma, or wisdom, not compassion. Why?

In Buddhism, we hear of “wisdom” and “compassion.” The two words often are mentioned together, such as in Jodo Shinshu, which focuses on Amida, the Buddha of infinite wisdom and compassion.

D.T. Suzuki produced many works and translated texts from Chinese, Japanese and Sanskrit literature. My dharma friend, Rev. Wayne Yokoyama, who has studied Suzuki’s works in-depth, told me Suzuki focused primarily on wisdom.

In Zen Budddhism, one sits quietly and meditates, searching for peace of mind or spiritual awakening. Sitting meditation in Zen is a tool or way of attaining awakening. One uses this tool or walks this path of practice. That is why Zen is sometimes described as a “self power” path, because it requires a person to have much dedication, focus and discipline.

According to the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism, a teacher gives students a riddle in the form of a question, called a koan, which they must solve on their own. They will sit in meditation pondering the question. Therefore, meditation is their tool or practice.

Sakyamuni Buddha sat in mediation under a tree when he awakened to Truth. The Zen tradition follows this meditation path as a way to attain spiritual awakening.

It’s interesting to note that later in his life, Suzuki translated a major Jodo Shinshu text, Kyogyoshinsho, written by Shinran Shonin. Jodo Shinshu emphasizes “Other Power,” or “Power Beyond Self.” This concept directly opposes the idea of “self-power.” Shinran wrote how he felt it was impossible to awaken to Truth through his own self-power efforts. Instead he relied on “Other Power.”

Suzuki was born in 1870 and graduated from Tokyo University. In 1900, he came to the United States and translated many Buddhist writings into English. Since he was a member of the Rinzai Zen tradition, the translations were mainly about Zen. He also taught at Columbia University.

In 1914, Suzuki returned to Japan, where he continued to translate Buddhist literature. He also taught at Tokyo University and Gakushuin University. In 1921, he became a professor at Higashi Honganji’s Otani University in Kyoto.

At the main Higashi Honganji temple, Rev. Haya Akegarasu asked Suzuki to translate the Kyogyoshinsho from Japanese to English. Shinran Shonin wrote the text, considered his magnum opus. Akegarasu hoped an English translation would help propagate Jodo Shinshu throughout the English-speaking world. In 1966, after doing the translation, Dr. Suzuki passed away in Kamakura, Japan, at age 95.

I think perhaps because Dr. Suzuki was originally from the Zen tradition, he was unaccustomed to discussing Buddhism in terms of Jiriki (self-power) and Tariki (other power). To me, Zen is a way of going (self-power) while the Pure Land tradition is a way of receiving (other power). Let me explain.

Zen is focused on the way “to” enlightenment through meditation. Jodo Shinshu is focused on what happened after the Buddha’s awakening.

Immediately after attaining enlightenment, the Buddha sat in meditation under the Bodhi tree for seven weeks, basking in the joy of his spiritual awakening. Then, he began to wonder if he should stay in that realm or return to the world to share the content of his awakening with others.

While in meditation, according to legend, the Indian god Brahma approached and asked three times for the Buddha to share the dharma with others. The Buddha realized that Brahma represented all human beings. If he did not share the wisdom he attained, people throughout the world could not be freed from their ignorance. Thus moved by great compassion, the Buddha rose from his seat and “returned” to the world. He first went to see his former companions with whom he practiced asceticism and explained the dharma.

To me, the Buddha’s “returning” sprung from Other Power, expressed as the dharma’s power, or compassion. Whereas, his search for awakening was a way of “going,” or self-power.

In Jodo Shinshu, our practice is listening to the dharma, receiving the teachings, reflecting on ourselves and our true nature. This is the way leading to the world of awakening. We are awakened by Other Power (Japanese: Tariki), which is expressed as Amida Buddha’s compassion.

In the Soto school of Zen Buddhism, founder Dogen, said to just sit and meditate on the dharma, then the dharma will come and embrace you, making your body and mind fall into the Dharma realm. In other words, just sit and the Buddha mind inside of you will awaken.

Doesn’t that sound like Jodo Shinshu? Dogen doesn’t mention “self-power” or “other power,” but he accepted the dharma as a power that awakens a person to ultimate truth.

Similarly, Jodo Shinshu teaches reliance on Tariki, other power. This power comes from the world of awakening. Reciting Nenbutsu, “Namu Amida Butsu,” is a manifestation of the dharma’s working, which is none other than Amida Buddha’s compassion.

-Rev. Kawawata is rinban (head minister) of Higashi Hongwanji Mission temple in Honolulu.