By Rev. Peter Hata

Currently, in response to the ongoing crisis surrounding the issue of immigration, there’s a certain poetic passage that is frequently quoted: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”

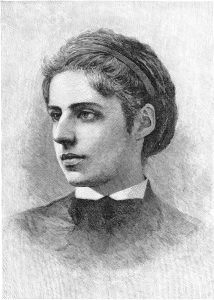

These lines are from the poem engraved on the pedestal that the Statue of Liberty stands on in New York Harbor. These famous lines, written by the gifted American poet Emma Lazarus in 1883, are not just relevant today.

(Emma Lazarus (engraving from Temple Shearith Israel))

They were relevant in Ms. Lazarus’s lifetime because just one year before she wrote her poem, the Chinese Exclusion Act became the first federal law that limited immigration from a particular ethnic group. However, her poem did not become well-known until about five decades later, after Congress had passed more exclusionary laws, such as the Immigration Act of 1924 that restricted Eastern European, Chinese, and Japanese immigrants. At the time, those that questioned such policies had also quoted Lazarus’s poetic lines. And now, in 2018, these same words are rallying people against the immigration policies of the current U.S. administration. The oft-quoted passage highlights the contrast between Emma Lazarus’s humanitarian vision of the nation and this administration’s often xenophobic rhetoric.

But are you familiar with the entire poem? The full poem, entitled “The New Colossus,” is a brilliant example of the 14-line Petrarchan sonnet form. In its first 8 lines, Lazarus clarifies the striking difference between this new colossus (i.e., statue), this symbol of equal opportunity and freedom, and that “old colossus,” what she terms the “brazen giant of Greek fame,” a reference to the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Unlike that ancient colossus, which was erected to commemorate the defeat of an attacking army, this colossus of the New World, whom Lazarus names the “Mother of Exiles,” holds a torch which glows with a “world-wide welcome.”

Then, in the last 6 lines, Lazarus gives the statue a voice which declares, “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” These words point to a vision of America more than the sum of its “storied pomp,” more than its battlefield victories, and though it is often interpreted as such, more even than an argument for diversity and inclusion and the millions of immigrants who have contributed to the strength and vitality of America. To think Lazarus’s poem is simply supporting “American greatness” is to make the Statue of Liberty into just another “brazen giant.”

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Actually, when I think about the compassionate vision that Emma Lazarus’s poem reflects, I can’t help but recall another statue Pure Land Buddhists are very familiar with, which is the statue of Amida Buddha in the temple altar. Interestingly, one of Emma’s contemporaries, the Harvard-educated poet James Russell Lowell, praised “The New Colossus,” saying the poem had given the statue its raison d’être. In similar fashion, there is a passage in the Larger Sutra that arguably gives the Amida statue its own raison d’être.

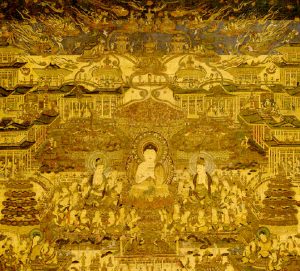

(Bodhisattvas visiting Amida’s Pure Land (Taima Mandala, ca. 8th cent.))

As we know, our goal as Buddhists is awakening. Stated in the symbolic language of Pure Land Buddhism, this is referred to as “birth in the Pure Land.” One of the most memorable descriptions of this birth is in the Larger Sutra [Part II, Sect. 27 in Hisao Inagaki’s translation]. Here, the sutra describes the innumerable bodhisattvas in the Pure Land. In the Pure Land, Amida, the master of the Land, says they all have the same aspiration, or hongan, that he has. However, the practice they must perform to fulfill their aspiration actually involves leaving the Pure Land and visiting and studying from—deeply appreciating—innumerable Buddhas. In this way, they perfect their Buddhahood, their birth in the Pure Land.

Nobuo Haneda has clarified this dynamic nature of Amida’s Pure Land: “Amida, whose essence is an ever-expanding spirit, does not allow bodhisattvas to make their comfortable dwelling place in the Pure Land. He encourages them to go out of the Pure Land, and to learn from all sentient beings, regarding them as Buddhas. In this way, the Larger Sutra talks about ‘true birth’ as birth in Amida’s Innermost Aspiration—in the spirit that endlessly goes out of the Pure Land to seek oneness with all sentient beings.”

And, in a similarly ever-expanding spirit, the “Mother of Exiles” in Lazarus’s poem cries out for the tired, poor, and huddled masses yearning to breathe free. In other words, it’s not necessarily the “desirable” hard-working “ideal immigrant” and not only immigrants of certain “approved” ethnicities; it’s especially those most in need that are welcomed. Clearly, the broad vision of America in Lazarus’s poem is one that transcends, like that of Amida’s Pure Land, liberal values of diversity and inclusivity, even as important as these are. Instead, the vision of America that the Mother of Exiles invites us to share in is a radical, transcendent one, which is why she cries out with “silent lips”; this is a truth-reality we’ve yet to actualize.

This vision is ultimately not a political point of view, but one that reflects the way things really are, which is oneness.

Rev. Hata is minister at Higashi Honganji Betsuin Temple, Los Angeles, CA

(Cover/Top picture: Artist’s depiction of the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty, 1886)