By Phillip Underwood

This is the story of how I ended up a member of the West Covina Buddhist Temple. It starts with the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

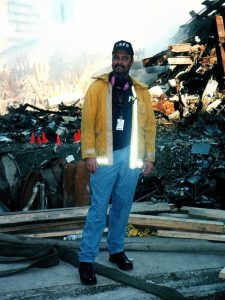

I was a captain for the Los Angeles Fire Department when I was called to respond to the New York City attack. I did not go as part of the Urban Search and Rescue Team. Instead I was committed to helping the rescuers themselves, or as we called it, “helping the helpers.”

Emergency responders—police, fire and medical—respond to every type of incident imaginable, including the smell of smoke, fender bender car accidents, severe injuries, mass casualties, train accidents, plane crashes, hostage situations, death, and more, including the death of one’s own crew member. Consequently, rescuers themselves are often left with emotions and memories from incidents detrimentally affecting them, which are commonly called posttraumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. Consequences can last for a lifetime.

In the mid-1980s, a Ph.D. named Jeff Mitchell developed a technique called Critical Incident Stress Debriefing, which was later called Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM). The idea was to address the problem of “who helps the helpers.” When exposed to unimaginable injuries or suffering in the course of one’s work, how do we process and react as human beings? Often the way people deal with this problem is through alcohol, drugs, anger and depression.

In 1985, Dr. Mitchell presented his idea to the LAFD and the concept was quickly embraced. I was one of dozens of members, uniformed and civilian, selected to undergo training in assisting, listening to and counseling uniformed members, following so-called Critical Incidents.

Critical Incidents include the deaths of children, deaths of other professionals, catastrophic injuries, severe burns, decapitation, and multiple deaths, such as by accidents involving cars, trains, and airplanes. Some of the team’s responses are automatic and others are requests made by concerned officers.

A primary benefit of CISM is that confidentiality is maintained because no reports are required of what was discussed, unless a member talks about hurting himself or herself or someone else. That person is referred to a specialist for follow up.

The day following the World Trade Center attacks, we were approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to go to the scene.

Our team of about 40 members consisted of trained uniformed and civilian department members, department clergy (Christian and Muslim), an overhead staff, and our director, Dr. Robert Scott. We also took two “interpreters,” who were LAFD uniformed members that were born and raised in New York. They proved valuable because New York emergency responders had rejected the concept of CISM in the 1980s. We were told that to them, counseling was “sissy stuff.” Their leaders thought “real men” didn’t need counseling or lectures; they just needed to do whatever made them feel good, whatever that was. Our interpreter’s helped us talk “New York talk.”

On Saturday Sept. 15, we departed from Los Angeles International Airport. After arriving, we took teams of a half dozen members to ground zero for 6-hour shifts over the following 12 days. The first people we counseled were members of the flight crew who brought us to New York. They had been grounded since landing in LA the day of the attack. They functioned well during the flight to New York until we flew over the city and saw smoke rising from the ruins at ground zero. That was when the flight crew “lost it.” As CISM first responders, we did what we could to help them deal with their emotions. We soon realized how far reaching and emotional this assignment was going to be.

My team consisted of five members, both uniformed and civilian: Captain I Howard Kaplan, Paramedic II Stacey Gerlich, Inspector II Aquil Basheer, Administrative Asst. Gwen Duyao, and myself. We visited ground zero six times, once for familiarization and five times to provide support and assistance. Our shortest shift was about five hours and the longest was almost 12 hours. Our shifts would begin any hour of the day or night.

It quickly became clear we weren’t going to be embraced by the FDNY. They ignored our efforts to connect as soon as they became aware of our purpose. I guess the 4’ X 8’ plywood sign announcing “Critical Stress Debriefing” was the wrong approach. We needed to think of a better method to get crews to talk to us. We found it during a meal break.

Adjacent to the World Trade Center on the Hudson River is a small marina accommodating several tour boats, private boats and police watercraft. A tour boat, the Spirit of New York, was a triple-decker being used to serve hot meals for workers. Gourmet and celebrity chefs prepared meals around the clock. During our meal break, two FDNY members noticed our LAFD uniform jackets. A brief conversation followed and the proverbial light bulb turned on in my head.

From that point, our tactic became what we called “picking their pockets.” We just sat in the dining area as though we were eating, making sure our LAFD insignias were visible. After ordering food, a search and rescue crew would come in, sit down, wait to be served, and then devour everything on their plates.

Up to that point, no one made any effort to communicate. But as soon as they finished, they usually acknowledged our presence and ask why we came to New York. We’d say, “If this happened in Los Angeles, wouldn’t you come help us”? They answered: “Absolutely.” Thus our conversation began.

We often asked, “When the first building came down and you knew your brothers were inside, what did you think?” Or, “When you first arrived at ground zero and saw the devastation, how did you deal with that?” We’d shut up and for the next 10 or 15 minutes, they expressed feelings about what was probably the worst day in their lives and we’d listen quietly, constantly encouraging them to express their feelings, and steering them away from talk about hatred or revenge. As quickly as they sat down, they’d leave, and we’d wait for the next group. We did this over and over again.

On the day before we returned to Los Angeles, our entire group took a cruise on the Hudson River, and during that 90-minute excursion we had a chance to reflect on our own feelings. That outing was one of the quietest boat rides I’d ever taken. We tried to make peace with what happened and what we experienced.

Personally, the feeling I had was more of a question. I knew and liked who I was before the attack, but was concerned that, even with my knowledge of CISM, I might not be the same person when I returned home.

I was afraid of what I might become, knowing that once before, my emotions were out of control when my mother died when I was 15. I definitely changed because of my experience in New York, but this time, my training helped me.

Now I’m at peace with who I am. I think I’m more tolerant with people that behave badly, unless they are doing it on purpose to harm others. I can’t judge others unless I also judge myself. Unknowingly, I guess this experience led me four years ago to wander into the West Covina Buddhist Temple, where I remain today a sangha member.

Phillip Underwood is a member of the West Covina Higashi Honganji Temple