By Father James Fredericks

(Editor’s note: In Buddhism, anger is one of Three Poisons of human nature; in Christianity, it’s one of Seven Deadly Sins. But anger can spur us to fight injustice, according to Father James Fredericks, which means, refusing to be angry also can be a sin. He asks, “What would Buddhists say?”)

Father James Fredericks:

Anger can be difficult to handle. We all know this. Anger can also be a sin. But this is not always the case. Sometimes God gives us anger as a gift. God wants to motivate us to work for justice.

I can think of lots of good reasons to be angry today. We have an economy that violates human dignity by concentrating more and more wealth into the hands of fewer and fewer people. We have a government that separates children from their parents as they plead for asylum at the border. We have families going bankrupt because they lack health insurance. And, of course, there is the atrocity that happened in Minneapolis for all the world to see. Sometimes I ask myself, “Why aren’t you more angry?”

Father Bryan Massingale, a Catholic theologian teaching at Fordham University, has useful things to say about anger in the theology of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Saint Thomas lived back in the 13th century, but what he has to say about anger is ready for us to put to work right away.

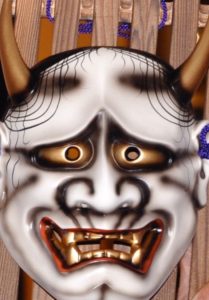

According to Saint Thomas, anger is one of the seven deadly sins. Anger must be included with pride, greed, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth as a vice that can entomb us, spiritually speaking.

Thomas also says there are three ways of committing the deadly sin of anger. The first is by “excess.” This is when anger becomes uncontrolled wrath. The second is by “misdirection.” This is when we direct our anger at the wrong object. Instead of dealing with the real reason for our anger, we “take it out” on some innocent person.

A third way we can commit the deadly sin of anger is by “deficiency.” This is when we refuse to be angry when anger is what is required of us in the face of injustice. Anger is not always a sin. Anger can be a passion that moves the will to seek justice. It’s a gift from God and a sign of the working of the Holy Spirit in our soul. This gift must be welcomed with gratitude and, I hasten to add, with humility.

Trying to use anger to accomplish justice is tricky. The “righteous” anger that moves the will to seek justice, as Saint Thomas understands it, very easily becomes “self-righteous” anger. I can tell you from experience that self-righteous anger never ends well. As I like to say, “The anger of the creature cannot hope to fulfill the justice of the Creator.”

Yet, we must recognize that, at important turning points in our lives with one another here on this earth, anger is given to us so as to move the will to seek justice. To refuse this gift is to commit one of the deadly sins – not by excess or by misdirection, but rather by deficiency.

What would Buddhists say about this? Is it possible to practice skillfully with anger? This question is all the more important to me given that “the anger of the creature cannot hope to fulfill the justice of the Creator.” I presume many Buddhists would prefer to talk about harmony that arises from the interdependence of all living things.

Years ago, I served as a translator and editor for Masao Abe (1915-2006), a Japanese Buddhist philosopher and exponent of Zen Buddhism. Abe-sensei used to talk about what he called “de-homocentrism,” in which the distinction separating human beings from the world is erased by the “true suchness” of all things. If there is nothing special about human beings, can we speak, any longer, of human rights? I agree: trees are important… but are they equally important as a starving child?

Abe-sensei wondered about being angry too. Instead of being angry, he wanted Buddhists to articulate a social ethics to help them respond to the suffering of the world. In Thailand, Buddhadassa Bhikkhu took a step in this direction with his proposal for a “dhammic socialism.” How does the dharma provide a vision of social relations, government, and people?

I’m interested in what a comprehensive system of Buddhist ethics for society would look like. This would be of benefit to me as a Catholic dealing with his anger. Moreover, I’m expecting that a Buddhist social ethics will have more to say about harmony than about justice. I am especially interested in how a Buddhist emphasis on harmony and interdependence might help me think about the environment.

In 2015, Pope Francis issued “Laudato Si’,” an “encyclical letter” in which he addresses climate change. (The title comes from the first two words of the Canticle of Saint Francis.) The letter’s subtitle is “On Care of Our Common Home.” Pope Francis wrote, “I urgently appeal, then, for a new dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet. We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all.”

The Pope is grafting concern for the environment with concern for human dignity. The Pope knows that our Buddhist friends have their own insights to share and he is eager to learn from them. Me too. We need to join together to be of benefit to one another.

There’s a lot to be angry about today… and it’s easy to be angry in all the wrong ways. Can we be angry together? And if this isn’t a comfortable fit for you, my Buddhist friends, can you at least teach me how to be skillful in addressing the suffering that’s all around us?

–James Fredericks is professor emeritus of Loyola Marymount University and a Roman Catholic priest in Northern California, who has been active promoting dialogue and cross-religious studies between Buddhists and Christians for many years.

Related links:

Buddhists and Christians: Dialogue of Fraternity by Father James Fredericks

Video lecture: Amida Buddha and Our Lady of Guadalupe by Father James Fredericks