By Rev. Ken Yamada

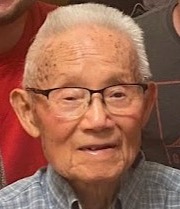

I’d like to tell you the story of a real-life superman. This superman did not work as a newspaper reporter for the Daily Planet, he did not live in a big city called Metropolis. He did not have a girlfriend named Lois Lane. This superman worked as a librarian, he lived in a town called San Luis Obispo in California and he had a wife named Fumiko. This superman’s name was Jack Noboru Kanbara, my father-in-law. Small in height, light in weight, mild in manner, sweet as apple pie, you couldn’t find a kinder, gentler man. Who would’ve thunk?

Jack wasn’t faster than a speeding bullet, he wasn’t more powerful than a locomotive, and he couldn’t leap tall buildings in a single bound.

But he did have the strength to overcome many great hardships in life. Born to a prototypical immigrant home in Stockton, California, he grew up with very little. He lived a hardscrabble childhood, like “the Little Rascals,” remember them? His father died when he was young, leaving his mother to fend for the family. She moved them to pre-war Japan. There, he endured the humiliation of being put back several grades with much younger classmates. After a year, mother returned to the States, leaving half the family and Jack, lonely kids in Japan. He gradually mastered his adopted language, Japanese, so well he became a school teacher there.

He was an American, but he was born to Japanese parents, so the Japanese Army drafted him near the end of World War II and he survived. His birth country, the United States, blocked him from returning home because he’d been an “enemy” soldier. He went to court, beat the government, and returned home.

He married the girl of his dreams, Fumiko. He attended UC Berkeley. He got not one, but two masters, degrees. He worked for decades as a librarian, helping legions of students. He provided for his wife and two kids. He was a dedicated husband, father and family man. He took his family, including son-in-laws, and grandkids, to Madonna Inn for Christmas dinner.

He knew history, he could talk politics. He learned book binding. He was a master gardener. He raised fruits and vegetables, grew flowers, succulents, and a multitude of plants, many of which he donated to Berkeley Higashi Honganji to sell at the summer bazaar. Every square inch of his yard, both front and back, was growing something. He made furniture—tables, chairs, nightstands, bookcases, a chase lounge. He built a deck in his back yard. He dug his own pond, laid the cement and installed a pump and fish. He made art from driftwood.

He was a master of recycling, before recycling was a thing. He made notepads from used paper, turned coffee cans, plastic jugs and milk cartons into planters. He threw away nothing, well almost nothing. He saved, and reused, wire ties, return envelopes, plastic bags from soil and fertilizer, old nails, and discarded wood.

It pained him to throw away food. He ate food past the expiration date, even when it wasn’t advisable, and composted the rest. He cut up old bed sheets to make cords for tying up newspapers.

He cooked and he baked. He made muffins and pancakes, even Gluten Free ones. Thanks Jichan. He overcame a weak and damaged heart through quadruple bypass surgery to live another three decades. He lived like a monk, eating super healthy, never straying. He delivered meals-on-wheels for years, often to people younger than himself.

There didn’t seem to be anything he couldn’t do. We called him “Jichan” (grandpa), always busy with something, puttering here and there, doing odds and ends. That’s Jichan.

When Fumi’s health declined and she needed help, he was there. He cooked, he cleaned, he helped her get dressed, gave her her meds and helped with the bath. He was there 24-7.

And this past year, after she was gone, he insisted on living on his own. Of course, he eventually needed help, but it wasn’t for long. He never wanted to trouble others.

To me, Jichan’s life embodied the Buddhist teachings, which in a nutshell, tell us this: No matter what life’s difficulties, no matter what life we’re born into, no matter our karmic conditions, no matter what suffering and difficulties we face, to carry on. To not be imprisoned by our pain, to not to blame others, to not sink into sadness, anger, or frustration.

To move forward, to do our best. To not get lost in a world of our desires. To be humble, to understand what’s most important, that is, our family, our friends, our community, everything around us, the earth. Because we are all connected.

To understand the preciousness of life, to appreciate the life we’ve been given. To live as fully and as completely as we can. This is the literal meaning of “Nirvana”—”to use up,” “to fulfill,” “to complete.”

This mission, given to each one of us by the universe, is what he accomplished during his 100 years on this planet. And that’s why I think Jichan was a true Superman.

All of us can be Superman, or Superwoman, or Supernonbinary, a Super person, just by living our lives as fully as we can, by rising above our ego and our selfishness and by seeing our connection to others, by appreciating the life we’ve been given, and by showing our gratitude to the people in our life, past and present.

Namu Amida Butsu

(Jack Kanbara passed away in February 2022 at the age of 100)

-Rev. Yamada is editor at Higashi Honganji Shinshu Center of America