By Rev. Ken Yamada

Years ago, Buddhism seemed irrelevant to me, so I quit. Instead I focused on making money, buying stuff and getting ahead. Looking back, I realized I was “asleep.” Fortunately, I “woke up.”

Let me explain. As a teenager, I loved Buddhism, thinking it held the key to the meaning of life and my fear of death. I read books, meditated and attended services and eventually took classes. In my twenties, I went to Japan and became ordained.

But after returning, I realized the priesthood wasn’t for me. Besides, I really didn’t understand Buddhism, especially Jodo Shinshu, with its crazy talk of “Pure Land,” “Amida Buddha,” “infinite compassion,” and what have you. None of it made sense so I quit.

I just didn’t quit the priesthood, I basically quit being “Buddhist.” Sure, if anybody asked, I’d identify as Buddhist, but I stopped going to the temple, I stopped reading Buddhist books, I stopped studying, I stopped everything. I had other priorities—getting a job, making money and building a career.

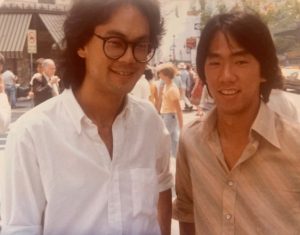

I became a journalist, first as an intern, then as a full-fledged newspaper reporter. I went where the job took me—Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco. Next was Silicon Valley as a business technology writer, then magazine editor. Eventually came a house and kids.

Then came the unexpected. My brother Bill, who was seven years older, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, a brutal and fast moving curse upending his life and mine. He asked for help so I visited him periodically in New York City, helping with his financial and legal affairs to provide for his young family.

Over the next several months, I witnessed his decline—the chemotherapy, the hair loss, the loss of appetite, the lapses in his thinking, the confusion, denial, anger, and finally, the acceptance. Many days he could only rest at home.

This was my older brother, with whom as kids I shared a bedroom, who helped me ride my first bicycle, whose plastic models of battleships and airplanes I envied, with whom I argued and fought as a teenager, who treated me to dinner and showed me the city the first time I visited New York. Now I was taking care of him. Illness twisted what was supposed to be. Life had turned upside down.

He was admitted to a hospice center, that place where people go to die. My mother and I visited every day. At first, he was talkative, asking about our day, about his symptoms, and about the effects of medication. Steadily, without fail, he weakened, his energy unstoppably draining from his body.

His appetite faded. I vowed to make him eat, to motivate and even force him, because people must eat to survive. The morning menu came, listing foods of the day. I read the items, one-by-one, commenting, “Orange jello! You like that” and “Meat loaf, try to eat a few bites.” My brother looked up and softly said, “You know, I can read.” He refused to eat.

I realized his body was shutting down, getting ready for that “next phase,” the “next world” or whatever. Nothing was going stop it.

His stomach inflated like a balloon. The nurse said something about swelling or bleeding. She asked permission to drain it and I consented. A tube was inserted and the big hump slowly shrunk.

That night, I returned to my hotel room. I felt totally helpless. I was there to “help,” but what could I do? Nothing.

Inexplicably, I got down on my knees next to the bed, put my hands together in “gassho,” hands in prayer position, and bowed my head. Slowly I said, “Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Amida Butsu.” Why? I don’t know. I had “quit” Buddhism, gave up on it more than a decade before. Now, I recited Nenbutsu, Amida Buddha’s name. It was a prayer—praying my brother wouldn’t suffer; praying I wouldn’t suffer. It was a plea for help. I said it because… what else could I do?

Impermanence had smacked me hard in the face. It’s a central teaching in Buddhism, which I had ignored. Now that painful reality confronted me.

My brother wasn’t particularly religious but he requested a Buddhist funeral. I contacted the New York Buddhist Church, to which I absolutely had no connection. Rev. Kenjitsu Nakagaki answered, who it turned out, was a friend of mine during my studies in Kyoto. He immediately visited my brother in hospice.

A few days later, my brother passed away. Rev. Nakagaki officiated the funeral. Many family and friends came. It was a fitting tribute. I truly appreciated this Buddhist priest who was there in my time of need.

On the plane ride home, the thought hit me—many people don’t think of a priest or a temple until they urgently need one, like I did. Likewise, for many of my family and friends, they’ll be in the same boat someday. I had the training, I had the qualifications. What a waste not to pitch in and help.

Moreover, I began to understand the importance of the Buddhist teachings, which somehow I missed before. Now I felt their preciousness in my bones.

And that’s how I ended up a Buddhist priest.

In the Larger Sutra on the Buddha of Infinite Life, which Jodo Shinshu founder Shinran Shonin revered, a passage describes how one day Ananda, the Buddha’s constant companion, notices a particular brilliance emanating from the Buddha. He asks:

“World-Honored One, today all your senses are radiant with joy, your body is serene and glorious, and your august countenance is as majestic as a clear mirror whose brightness radiates outward and inward. The magnificence of your dignified appearance is unsurpassed and beyond measure. I have never seen you look so superb and majestic as today… For what reason does his countenance look so majestic and brilliant?”

The Buddha answers: “Tell me, Ananda, whether some god urged you to put this question to the Buddha or whether you asked about his glorious countenance out of your own wise observation.”

Ananda replies: “No god came to prompt me. I asked you about this matter of my own accord.”

The Buddha says: “Well said, Ananda. I am very pleased with your question… Ananda, listen carefully. I shall now expound the Dharma.”

Ananda replies: “…With joy in my heart, I wish to hear the Dharma.”

I felt like Ananda. He had accompanied the Buddha on many travels, yet only on that particular day he noticed the Buddha’s brilliance. That brilliance, which was always shining, is the wisdom and truth of the Buddha dharma, the Buddhist teachings. He hadn’t noticed, until now.

I studied the Buddhist teachings but didn’t appreciate them. Only after experiencing my brother’s death did they begin to make sense. Now I appreciated their truth and wisdom.

Ananda said, “With joy in my heart, I wish to hear to hear the Dharma.” I feel the same. That’s why I returned to Buddhism. “With joy in my heart, I will listen.”

Rev. Yamada is editor at Shinshu Center of America