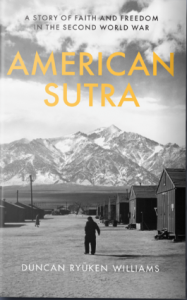

Professor Duncan Ryuken Williams’ recently published book American Sutra has been attracting much attention for its description of Buddhism in World War II internment camps. We asked Professor Williams more about his book, its origins and its message for today’s world.

What prompted your interest in writing about Buddhism in internment camps during World War II?

As someone who grew up in Japan until age 17 and studied pre-modern Japanese Buddhist history for my graduate work, I had no family connection or scholarly interest in the Japanese American incarceration. After defending my Ph.D. at Harvard, I came across a Japanese-language diary written by a Buddhist priest in the Manzanar camp. He was the father of my graduate school advisor, Professor Masatoshi Nagatomi. Asked to translate the diary, I had to take a crash course in the war and Japanese American history. The vivid description of camp life and how Buddhism helped people persevere under difficult circumstances inspired me to learn more and also accept more requests to translate other diaries of Buddhist priests. This became a project that took more than 17 years to complete, including interviewing more than a hundred camp survivors and writing a book accessible to a general readership.

What was the most surprising thing you found in your research?

A religion such as Buddhism is a refuge with teachings and practices which help people get through difficult times. Many Buddhists during the war turned to their faith at a time of dislocation and loss. In talking about its importance, some people said they practiced Buddhism due to their incarceration, rather than despite the circumstances. Drawing on the classical Buddhist image of a lotus flower blossoming above muddy waters (the flower representing the Buddha’s awakening/liberation transcending the “muddy waters” or the world of suffering), some of them interpreted their difficult circumstances like the mud’s nutrients that gave strength to the growth of the lotus flower. They found freedom in the very midst of incarceration.

Nowadays, Buddhism enjoys an image in our popular culture of great appeal to anyone seeking less stress, peace of mind and a more compassionate way of life. However in your book, you document that prior to and during World War II, Buddhism was viewed with suspicion and was even considered anti-American. How do you explain the change in perception?

Just as Japanese Americans who served in the U.S. Army during the war changed perceptions within the military about loyalty and willingness of Japanese Americans to sacrifice for their country, the simple persistence of the Japanese American community in their faith was testament, not only to adherence to the Buddhist teachings, but to America’s promise that religious freedom was a fundamental part of being American. During the post-war resettlement period and the turn towards Asian religions by non-Asians in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, Japanese American Buddhists were key players in welcoming convert Buddhists to the sangha, the Buddhist community. The transformation of the perception of Buddhism from being a threat to national security to a peaceful religion that contributes wisdom and compassion to the American religious and cultural landscape took some time, but it’s amazing that in a generation or two, it’s possible to shift prejudices through knowledge and understanding.

During these times of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” some people still say the incarceration of Japanese Americans was justified. Have you received any pushback or criticism of your book?

Thankfully, reception of the book has been great. By laying out what happened with strong historical documentation and evidence, it’s hard to dismiss this episode in American history as one justified by “military necessity,” as the 1943 Final Report by Lt. Gen. John DeWitt claimed. When I speak about how babies and toddlers at orphanages were rounded up as part of the forced removal from the Pacific Coast in 1942, it becomes hard to justify that such children could really conduct espionage and sabotage, and that they constituted a threat to the nation.

Do you think the events of World War II made Buddhism evolve into a stronger or weaker presence in the United States?

On one hand, pressure to assimilate towards a presumed Anglo-Protestant normativity led in some circumstances to people converting to Christianity. Those people who remained Buddhist during the wartime years made a recommitment to the sangha and what it stood for. In a way, through the crucible of war, the process of Americanizing Buddhism was hastened and so it could be said Buddhism was strengthened for some members of the tradition.

The stories and anecdotes you tell about discrimination, racism, and religious suppression seem eerily prescient to today’s news about attacks against Muslims and internment camps for migrants. Do you see the events you documented and today’s events related in some way? What are the biggest takeaways you would like readers to learn from American Sutra?

What happened to Japanese Americans during World War II came from a certain idea of American belonging that conflated race and religion with inclusion/exclusion in American life. Because Japanese American Buddhists were neither white nor Christian, they became easy targets. Unfortunately these types of conflations and understanding of who belongs seem to be enduring challenges for the United States. Whether it’s race (on the southern border with Central American migrants) or religion (with the Trump travel ban), these factors seem to come to the fore whenever discussions of immigration and inclusion/exclusion are raised. Buddhists have a worldview that is pluralistic in nature and we can draw on past history to point to the importance of an America that is more inclusive and religiously free.

Williams is a professor of religion and East Asian languages at the University of Southern California and director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. Previously, he held the Shinjo Ito Distinguished Chair of Japanese Buddhism at University of California, Berkeley, and served as director of Berkeley’s Center for Japanese Studies. He also is an ordained Soto Zen Buddhist priest.

-Rev. Ken Yamada, editor, Shinshu Center of America